Billy Baxter (Harrison William Baxter IV) didn’t know shit from Shinola as my father would say; so how in the world did he make it to as the CEO of a multinational energy company?

There are only two explanations – the first is that the genetic bits of Great Uncle Harrison Baxter III eventually kicked in and Billy, although he didn’t understand the sudden inspiration and driving ambition that hit him in Senior Year in high school, he couldn’t resist the inner urge to create, produce, and succeed.

Although the chances of as few stray fragments of the elder Baxter finding their way into Billy’s DNA were slim indeed, it was certainly possible. Harrison Baxter was last in a distinguished line of Wall Street Baxters. Harrison I advised J.P. Morgan in the laissez-faire days of American capitalism, bought and sold railroads, shipyards, and steel mills; amassed the wealth of Croesus for his patron, and protected his investments from Park Avenue to Jekyll Island.

Harrison II came of age just before the Great Depression but preternaturally astute in matters of finance, saw the Crash coming and quickly moved the family’s fortunes to safe havens abroad.

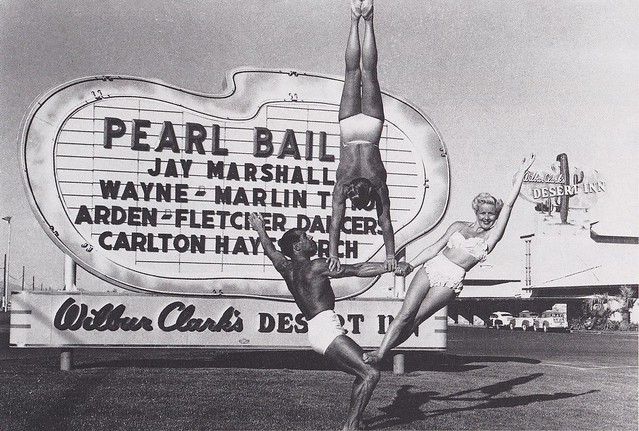

Harrison III invested millions with Meyer Lansky and his early investments in Las Vegas paid off for decades. Lansky and the Mob provided the muscle, and Harrison Baxter provided the uncanny advice necessary to keep one step ahead of the IRS.

So, whatever bits got passed along the Baxter line could very well have been responsible for Billy’s sudden and welcome coming of age.

On the other hand, all the Harrison Baxters were wanton philanderers, and the family tree had more illegitimate offshoots than the courtiers of Elizabeth I. Unlike these noble wanderers, however, who bedded the daughters of high-borne families, the Baxters were known to frequent the brothels of New Orleans, New York, and – surprisingly – Detroit. The Motor City is now only known for its crime, dereliction, and corruption; but in the heyday of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, it had a lively night life – cabaret, dance halls, and women of the night imported from Pigalle and the grand boulevards of Paris.

No one was quite sure where Harrison Baxter IV (Billy) came from since the family with all its wealth, power, and political influence managed the genealogical history of the family with care and discretion. No one cared who was legitimate or not – boys will be boys after all, and the Baxters were legendary Lotharios – and the Baxter treasury was well-husbanded and kept intact. It is safe to assume that even with all the sullying of the bloodline with hussies from the Moulin Rouge, some of the strands of genius could have made their way through the years.

The second possibility is even more likely. Tolstoy in War and Peace expounds at length on his theory of ‘accretive history’. All actions, whether by Napoleon or the soldier in the ranks of the Tsar, are conditioned by a bewildering and indecipherable cascade of past events and influences. French historians opine that if Napoleon had not been indisposed with a bad cold on the day of the Battle of Borodino, things might have turned out more favorable. He was so fogged with rheum and so rattled by cough and congestion that he could not think straight and uncharacteristically misjudged the moves of his opposite number, Prince Kuznetzov.

Tolstoy and a legion of more rational historians debunked the Great Man theory, and dismissed the idea that the course of history was determined by individuals alone. Not only was Napoleon’s valet responsible for the defeat at Borodino because he had forgotten the Emperor’s waterproof boots (he was distracted from his duties by his unfaithful wife), thus obliging him to ride in wet leather and get chilled, but every general, colonel, and subaltern under Napoleon’s command was equally driven by past history, circumstances, and luck.

A generation or more had passed between Harrison Baxter III and Billy, and the family had squandered its fortune, lost its place in society, and were as negligent and irresponsible as the Puerto Ricans in the North Ward. The upper classes of New Brighton tolerated Billy’s family because of who they were, not what they had become. Unpaid dues at the Shreve Meadows Country Club were overlooked, bar tabs were paid for by 19th hole social climbers who thought there was still some currency in the Baxter name, and Henrietta and Bart Baxter, Billy’s parents, went on their drunken and profligate ways, drawing down the final sous in the Grenadian Bank of Scotland where the family’s money had rested since the halcyon days of the turn of the century.

Billy, as most children, did what his parents told him; and followed their example in all else. As a result he was an indifferent student, an adolescent wastrel, and according to all his teachers, bound for nowhere. But, as Tolstoy predicted, his ultimate and most important actions were conditioned by the chance interactions of peers, cohorts, friends, and random actors from Broad Street to Broadway.

Belinda Granski was one of the few girls who ever frequented Jimmy’s Smoke Shop, a seedy downtown bus station-cum-girlie magazine depot. She went there to pick up New York papers for her father, but lingered among the candy racks to watch the men sidle back to the magazine rack, flip through the latest editions of ‘Pussy’ and ‘Come’, and leave with a pack of Luckies. She was the inspiration for Michael Haneke’s La Pianiste, a story of a sexually frustrated piano teacher who cruises porn shops by night. Haneke had been an exchange student in New Brighton as a very young man, and the image of Belinda in the seedy, foul-smelling, station-depot stuck with him until he made his film.

Billy Baxter met Belinda at Jimmy’s and they started a torrid small-town affair. Belinda was not much on looks or class, but she was born with emotional antennae as sensitive as the silkworm moth which can smell the scent of one molecule of female hormone from a mile away. She sensed that Billy was special, and whether or not she picked up on free-range molecules from Grand Uncle Harrison’s DNA (unlikely) or understood that his restlessness was because of a dormant talent, she said, “Billy, you are a very special man; and you will do great things in your life”.

Billy woke up from his intellectual and emotional sleep and began to pay attention to money, success, status, and social position. At the same time, other random, totally unpredictable happenings helped to propel him along his now anointed path. His country day school mistakenly ratcheted up his grades from low C’s to A’s, and because his mother was sleeping with the academic dean, his recommendations to Andover, Exeter, and Groton were superlative.

He took a minor role in a school production of Troilus and Cressida – that of Cressida, thanks to the avant-garde director of the play, himself a refugee from the Castro – and received rave notices from the Boston Globe whose drama critic was the lover of the play’s director.

Billy paid no attention to his dramatic acclaim; but his name and that of his family got bruited around Beacon Hill, and his acceptance at Harvard was a done deal.

From then on, Billy’s native abilities took over. He finished Harvard in three years, went on to Harvard Business School, picked up a law degree at Yale, and got a job with Goldman Sachs. By this time he had a renewed interest in the doings of his ancestors, and decided that he was more cut out for the rough-and-tumble world of business than Wall Street. In a short time he had made it to the top of the corporate ladder.

Those of us who went to country day school with him were amazed at his various successes. He was voted the least likely to succeed, a category that was later removed from graduation hijinks at the beginning of the PC era. He had no social graces, no athletic ability, and he was clueless about girls. We were all looking forward to seeing him again at the 40th reunion of our class. For all intents and purposes he had not changed a bit. He still had that ne’er-do-well, doofus, shambling walk and adolescent shyness; and we liked him. We never grilled him about his scrambles and Wall Street wars, and were content just to share stories about raiding the Kotex from the girls bathroom, hot Nancy Beene, and Mr. Strumple’s cyclonic sneezes.

As I reread War and Peace and come across Tolstoy’s passages about historical conditioning, the interconnectedness of random events, and the demythologizing of genius, I think of Billy Baxter. Billy in fact did know shit from Shinola, but my father died before he could see him as the star witness at a Congressional hearing on wealth management and the law.

Billy died relatively early – in his late 60s – and I hope that he had one of Tolstoy’s famous deathbed epiphanies. There are no more chilling but insightful passages in all of literature about death and dying than those of Prince Andrei and Ivan Ilyich. We will never know whether at the moment of his extinction he had insight and illumination or reverted back to his clueless days in New Brighton.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.