We come by this naturally. Wealth was a Puritan virtue, a sign that God had conferred heavenly status and material well-being; so why should an early American be a Scrooge or Silas Marner? A century later Immigration added fuel to the American ethos. Southern Italians, Jews from the shtetl, Irish escaping the potato famine came to America to search for a better life. The streets were paved with gold, and if the new arrivals at Ellis Island had a rude awakening when they first saw the tenements of the Lower East Side, that initial disillusionment didn’t hold them back. Jews put a few rags together, became tailors, shop-owners, clothiers and furriers, and soon made and spent money like native Americans. Things weren’t everything, but they most definitely were important.

Except for that cultural cleansing of the Augean Stables – the Sixties – when American society questioned materialism, we have never veered from our chosen path. In fact there was nothing like the excess of the 80s to get us back on the fast track. A great helping of chocolate cake with heaps of frosting after a decade of grainy muffins and raw vegetables. The Sixties were an aberration, a curiosity, a blip on the radar, an eddy in the mainstream.

Few Americans are materialists who have turned the quest for material goods into a religion, or a search for the Holy Grail. Most of us simply enter the perpetual cycle of desire, expectation, purchase, disappointment, and desire again. Such modest materialism doesn’t hurt anybody and is the engine of the American economy. Any Sixties leftovers who complain about the endless aisles of razor blades, shampoos, crackers, soft drinks, and tuna fish as an unnecessary and expensive diversification of simple products still don’t get it. Giant and Safeway are modern temples of material success and bounty. Consumer choice is a proxy for freedom of choice. Product diversity is a celebration of individualism. Aisle markers – Paper Goods, Cleaners, Beauty Products, Cat Food, Ice Cream, and Soft Drinks – are Stations of the Cross.

Materialism in one form or another, from one extreme to the other, is in our blood.

A co-traveller of the Sixties, largely unreconstructed, believes that his patronage of farmers markets and purchases of Opus One, Petrus, New Zealand lamb shanks, and sushi-grade tuna are not expressions of materialism but good taste. His ‘purchases’ of Jean Georges and Le Bernardin fall into the same category – highly selective, occasional forays into top international cuisine. For him materialism is for others – a clothes rack of inexpensive dresses, a closet full of shoes, knick-knacks, tchotchkes, and knock-off Limoges dinner plates. Yet his non-essential purchases – the key indicator for materialism – are as proportionately high as anyone. He is just fooling himself.

Rebecca Rosen writing in The Atlantic (8.2.14) on materialism says:

It's been the refrain of behavioral economists and, in my case at least, my wise husband for years: Spend your money on experiences, not things. A vacation or a meal with friends will enrich your life; new shoes will quickly lose their charm.I am not sure to which school of economics these academics belong, but they have not spent enough time in the real world. Fashion, for example, is perhaps the most obvious and glamorous example of materialism. Women do not need so many outfits, but the best dressed, chic, and hip will all say that they dress for themselves as well as for others. Looking good is a matter of grace, elegance, sophistication and personal style.

Italians may have the best and most finely-tuned sense of style – bella figura. Everything has to look good. Whether it’s the Milanese industrialist, a Roman actor from Cinecittà, or Mafia don from Palermo, stepping out in style is de rigeur. Italian automobiles have always been prized for style if not for performance. Italy is one stylish country, and material things are essential to it. Of course, one eats well in Italy, but the elegant meal and the Ferrari are all part of the same stylish ethos.

Christmas is about things. First baseball glove, first two-wheeler, and first set of combat figures. Christmas was poinsettias, High Mass, roast chicken dinner, and family; but it was first and foremost about toys. Some of that luster has been lost in the profusion of cheap plastic throw-aways and electronic gadgets; and Christmas has indeed become materialistic. However it was not always so even though material things were at the heart of the celebration.

The question raised by Rosen is whether or not material things can make you happy, and she cites recent research by Guevarra and Howell:

In many studies, participants are asked to think about material items as purchases made "in order to have," in contrast with experiences—purchases made "in order to do." This, they say, neglects a category of goods: those made in order to have experiences, such as electronics, musical instruments, and sports and outdoors gear. Do such "experiential goods," say Guevarra and Howell leave our well-being unimproved, as is the case with most goods, or do they contribute positively to our happiness?

In a series of experiments, Guevarra and Howell find that the latter is the case: experiential goods made people happier, just like the experiences themselves.In other words a pair of hiking boots are a better buy because they are instrumental to a higher good – hiking in the woods. A Solingen steel kitchen knife adds to the pleasure of preparing food and eating a nice, finely-sliced veal piccata. A wrist watch only tells the time and does not enable onward activity; nor does a tie clasp; or flower vase.

Some 'collectors' see an even higher order to certain things - a subtle, finely chiseled, enigmatic10th Century Indian sculpture. An Early American silver salt cellar, an Edo Victorian Japanese print, an Audubon painting of egrets, and a Russian hand-painted and lacquered jewel box.

In other words we are all good materialists. We purchase clothes, food, silver, Persian carpets, and antique prints because they remind us that the world is not all dross and bottom line.

A garden is a composite of an old cherry tree, new magnolias, a holly tree that has grown over the trellis and arbor, petunias, daisies, chrysanthemums, and skip laurels. It is only a ‘thing’ in the broadest sense of the term, but it was desired and purchased like anything else.

It is materialism itself which deservedly comes under criticism – the rampant and excessive purchase of things which add little permanent value, are not ‘enablers’, nor expand taste and experience. Yet where does one draw the line? The living rooms in some houses are filled with ceramic cats and in others crowded with cheap trinkets and souvenirs from past vacations. Walls are covered with cheap, Fisherman’s Wharf seascapes, coffee tables cluttered with mass-produced glass figurines, and furniture accessorized with throw pillows and stuffed animals. Are these not the equivalents of a 10th Century Buddhist head?

Rosen returns to her particular view on material value and one suggested by the researchers Guevarra and Howell. Enabling things are better than static, uniform ones because experiences are better than observations or contemplation:

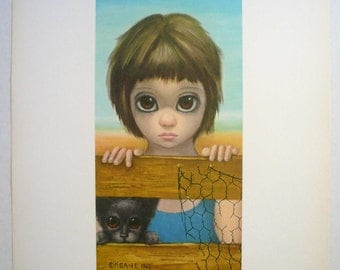

What is it about experiences? It's not the fact of having an experience per se but that experiences can "satisfy the psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness." Talking to friends, mastering a skill, expressing oneself through art or writing—all of these provide a measure of fulfillment that merely owning a thing cannot.This, of course, is not true at all. Material possessions whether high-toned or –low are essential and integral parts of our lives. ‘Materialistic’ is the pejorative term we give to the possessions of others which we think are in bad taste; but all of us make purchases based on background, class, education, and upbringing. Living rooms are very good indicators of where you belong. It is hard for anyone who has a Braque lithograph on the wall not to sniff at Joe the Plumber’s choice of a Keane reproduction.

It is nearly impossible for anyone who has eaten at Lyon’s finest Michelin starred restaurants to understand why anyone would go to Olive Garden.

Thorsten Veblen is famous for his theory of Conspicuous Consumption - a phenomenon which is as American as apple pie. Things define us more than behavior, attitude, or politics, Veblen observed. How right he was, and American consumerism and the status that it has conferred for decades confirms his conclusion.

Rosen is right to make a distinction between types of things, but wrong in putting so much credence in Guevarra and Howell. Things, as Veblen noted, define us; and each of us expresses that definition in different ways. It is elitist - to say the least - to make qualitative judgments about consumer choice; and wrong to criticize America for its consumer culture.

The French have always been admired for their style and elegant taste; and French women regardless of income have always prided themselves on looking good. A Frenchwoman of modest means has one good dress – an expensive, couturier design – but would rather have that one expression of good taste than ten cheaper ones.

America in comparison to France is very much a materialistic culture, and yes, we have a tendency to overvalue things at the expense of experience; but materialism does indeed keep the economy humming; and beautiful things – fashion, art, pottery, carpets, and sculpture – are happy by-products.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.