Wendell Roberts worked for many years in the field of International ‘Development’. He always put quotes around the term because he said that nothing ever got developed except the Swiss bank accounts of corrupt dictators.

Most projects to help the poor were designed because of national interest group pressure. The breast feeding lobby was well-known for its hectoring of Congress to do something about the world’s women. The Vitamin A, D, E, folic acid, and iodine lobbies were no less insistent, and relentless in their demands that Congress stop the invasive and unnecessary slide of the poor into mental deficiency (iodine), wasting anemia and fetal distress (folic acid), perennial infections (Vitamin A), and immune deficiency and rickets (Vitamin D).

Few if any of these campaigns made any sense. Bottle-feeding was verboten, said breastfeeding advocates who zealously protected their turf against Nestlé's and rejected working mothers’ claim that the bottle offered them the same independence that American suffragettes had sought. Bangladesh was a country of mental retards, said the iodine lobby, although the relationship between iodine deficiency and intellectual capacity was far from settled science. The conclusion that HIV/AIDs was ‘everyone’s disease’, a politically motivated and epidemiologically flawed approach to the disease, assured an inefficient use of resources and guaranteed little positive impact.

In all cases of international ‘development’, the only thing certain was that government officials, knowing which side of their toast was buttered, got rich.

“The poor are all the same”, said Roberts. “They live in mud huts and shanty housing, eat poorly, have too many children, are uneducated, and are ruled by priests, medicine men, and corrupt politicians.”

It was no surprise that international ‘development’ did not work. “Ignorance and shamanism are alive and well in the bush and in Foggy Bottom”, he said.

All of which brings me to ‘poverty voyeurism’, organized tours of the slums of Africa for those wanting a new foreign adventure, a renewed commitment to progressive ideals, or both. Surprisingly there is an unmistakable progressive cachet to Treichville, Soweto, Kamkunji and a thousand other slums in Africa, Asia, and Latin America despite the fact that poverty, as Wendell noted, is a pathology, and unless you are sick with the disease, you will never know how bad it feels.

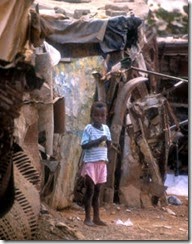

The tours, of course, are carefully designed to avoid the worst and the best. Too much misery and few tourists will want to visit. Too much normality and accommodation and they won’t feel they got their money’s worth. In fact most successful tour agencies maintain a network of advance team who visit the slums and rate them according to ‘appropriateness’ – not too hot, not too cold, but just right. Poor without desperate poverty; uncomfortable living conditions without infestation and misery; inadequate sanitation but no foul, stinking open sewers. Shabbily-dressed children, but no naked, grimy ones.

Mwomba was one such slum. When the African City Tours advance team first visited Mwomba, it was pretty much like the many others he had seen, but he noticed a particular entrepreneurial spirit on the part of community leaders. They saw right off the bat that there was money to be made - maybe not direct cash transfers for ‘renting’ the slum or lending it out; but perhaps for renovation or rehabilitation. There was always unofficial money to be made from contractors and service agencies. European and Scandinavian voluntary agencies, flush with donor money, had flooded the country with no-strings-attached resources, and communities like Mwomba had made out like bandits. This private tour agency would not be any different.

The African City Tours advance man laid out the ground rules for collaboration. He showed them pictures of the types of neighborhoods, houses, lanes, and facilities he wanted to include in the tour. He showed them pictures of adults and children from other African cities and illustrated the features of dress, coiffure, and demeanor that he was looking for. When the chief of the slum objected to the rather shabby dresses worn by the girls in the photographs, the team leader said, “It’s only for a few hours; and we will buy new dresses for all the ‘actors’ in our production”. A knock-off Armani suit made in Morocco was thrown in for the chief for good measure.

The advance team left nothing to chance. He and the Mwomba leaders worked out a very organized program – time of day, route, rest stops, and photo shoot locations. When the leaders suggested a meal, the team leader demurred, knowing that no American tourist, no matter how compassionate and forgiving, would ever eat local food; but in keeping with the Armani suit, he wrote a banquet dinner for all community dignitaries in the budget including imported beer and South African beef.

The advance team was very diligent, and made a number of trips to Mwomba to be sure that the preparations were going according to plan; and to his delight, there were only a few glitches in the program. Unusually severe rains had turned some of the picturesque lanes into muddy cow paths, and a minor epidemic of dengue threatened to delay the first visit; but in the end, all worked out well. The American tourists were delighted with the visit. ‘Delighted’ is perhaps the wrong word, since the tour had been designed to leave the visitors with a sense of empathy if not pity. The goal was for them to get back on the bus quietly and with a profound sense of respect for the disadvantaged friends they had just left, not to be overjoyed.

African City Tours made more money than they ever imagined from this new enterprise; and those young associates working for the company felt accomplished in cross-cultural communication, negotiation, management and budget, and above all public relations. Some even likened their work to theatre. They were hired to put on a good show, and like any Broadway producer had to get the actors, lights, scenery, and music right. They understood the narrow window opened for them; and they were mindful of excess (melodrama) as well as too much understatement. There could be nothing false and kitsch, but nor could any real misery, penury, and suffering make its way onto the stage.

The company was particularly good at production, and although school was not in session during the high tourist season, it arranged for ‘Going to School’ and ‘Coming Home from School’ scenes – pressed uniforms (well used but presentable), book bags, and shabby, worn, and badly scuffed shoes. It managed every other aspect of community life with a similar attention to detail.

African City Tours learned quickly that they could not invest in tour communities within the same city. In the case of Kinshasa, rival neighborhoods organized armed gangs to terrorize potential competitors. Word travelled fast about the company’s plans for investment and competition was fierce and bloody. The price of the tours was higher than the company wanted because of the time and resources required to service communities in different cities and countries, but thanks to careful resource husbandry, they did fine.

The company was Internet-savvy and leveraged their profits through partnerships with progressive organizations in the US. Clients of African City Tours who had been moved by their experience in Mwomba received emails urging them to give to ‘Progressives For African Development (PAD)’. In turn PAD recommended African City Tours to all its donors for ‘A close-up view of the real Africa’. In short, everyone made out – African City Tours, PAD, and the leaders of Mwomba.

An inordinate amount of attention has been paid to the Hollywood attention-grabbers and faux progressive ‘Compassionates’ like Bono, Madonna, Angelina Jolie, and Gwyneth Paltrow. Their concerts, tributes, and appeals are nothing compared to the burgeoning business of private poverty tourism.

To paraphrase Wendell Roberts, “If you’ve seen one slum, you’ve seen them all”; so African City Tours’ marvelously ingenious theatricality should be applauded. No one wants reality, after all, let alone a repetitious, monotonous one; so better a gussied, transformed, idealistic version. And if it makes money, so much the better.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.