NASA, www.independent.co.uk

The most frightening nightmare that Libby Cullers had ever had was drifting alone in the farthest reaches of space. Here there was no light, no sound, no stars, asteroids, distant planets, or comets. She was drifting, at least she thought so since there were no reference points for her to be sure. She might be tumbling, but in the empty, gravitation-less space, she could also be absolutely still.

She knew that she was not blind because she could see the inside of her helmet; and she was not dead because she could hear her breathing; but any sense of being, personality, purpose, or meaning was gone. The aloneness was suffocating. She wanted to grasp something, anything – the ship, Earth, her parents, some bit of an asteroid to confirm that she was still she.

This dream is not common, but common enough and so obviously existential in origin that many professional papers have been written about it. It is all about death, modern Freudians conclude. However, although Libby Cullers’ dream was indeed about death and in minutes before dying a look into nothingness, it was no sign of mental disorder or neurosis. It was a precocious look at mortality.

The only good thing about the nightmare was waking from it. For a few minutes she was still drifting in space, still gasping and frightened; but soon the features of her room - the stuffed animals, lace curtains, and rims of dust around the teapot and flower vase – took the place of the dream – and she was never happier. Then Phase III arrived – the silliness of it all, the very bourgeois retreat from the emptiness of space to her little home, capitulation, and she couldn’t believe how stupid she was.

Libby had read all her brother’s comic books about space travel, asked for a telescope for Christmas, and read Jules Verne and every other book in the New Brighton Public Library on astronomy, space travel, and the possibility of intelligent life in the universe.

One of her favorite books was H.G.Wells’ The Time Machine, especially the last scenes in which the Time Traveller stands on the edge of entropy – a cold, motionless sea, a flat, cold, featureless landscape; a sky with a dim, pale sun low over the horizon. She read these passages first as a young girl and then many times later as an adult, especially when she was having her nightmares. At first she was worried that the book would provoke bad dreams; but then thought that perhaps Wells’ story would take the place of the grimness of her nightmares.

This might have been a solution if Libby’s nightmares had been a symptom of a psychological disorder – a neurotic fear of death, for example; or an inability to live in the present – but they were nothing of the sort. The nightmares were real and existential.

Suddenly I noticed that the circular westward outline of the sun had changed; that a concavity, a bay, had appeared in the curve. I saw this grow larger. For a minute perhaps I stared aghast at this blackness that was creeping over the day, and then I realized that an eclipse was beginning...

'The darkness grew apace; a cold wind began to blow in freshening gusts from the east, and the showering white flakes in the air increased in number. From the edge of the sea came a ripple and whisper. Beyond these lifeless sounds the world was silent. Silent? It would be hard to convey the stillness of it. All the sounds of man, the bleating of sheep, the cries of birds, the hum of insects, the stir that makes the background of our lives—all that was over.

As the darkness thickened, the eddying flakes grew more abundant, dancing before my eyes; and the cold of the air more intense. At last, one by one, swiftly, one after the other, the white peaks of the distant hills vanished into blackness. The breeze rose to a moaning wind. I saw the black central shadow of the eclipse sweeping towards me. In another moment the pale stars alone were visible. All else was rayless obscurity. The sky was absolutely black. (H.G.Wells, The Time Machine)

Libby’s mother had read her Wordsworth’s, Ode Intimations of Mortality from Recollections of Early Childhood after she had told her of her nightmares. Wordsworth had written of childhood innocence and said that “nothing was more difficult for me in childhood than to admit the notion of death as a state applicable to my own being”; and the fact that her daughter had jumped decades to glimpse the mortality that Wordsworth had only seen as an adult, worried her.

The rainbow comes and goes,

And lovely is the rose;

The moon doth with delight

Look round her when the heavens are bare;

Waters on a starry night

Are beautiful and fair;

The sunshine is a glorious birth;But yet I know, where'er I go,

That there hath pass'd away a glory from the earth.

Of all the lines of innocence of the poem, these were the ones that Libby most remembered. In her nightmare glory had long since passed away from the earth and she, like the Time Traveler, was on the cusp of extinction. The defiant lines of Dylan Thomas (Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night) meant nothing to her:

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

As a young woman far from death she had foreseen that her end would have no blaze, no defiance, nor any comforting Wordsworthian moments of calm reflection, just a dark, cold, and terrifying emptiness.

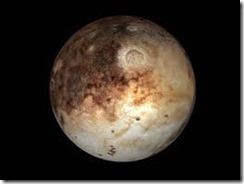

I have thought a lot about Libby Cullers in the last few days (July 2015) because a NASA space vehicle – after almost five billion miles and a nine-year trip, has just sent back close-up photographs of the dwarf planet Pluto.

To space scientists there was no closure – all planets of our solar system had been visited and photographs recorded – but to me the images simply marked the farthest limits of our known world. What lay beyond was far more fascinating. What would we find if New Horizons kept on going? At some point it would reach Libby’s nightmare – an absolute entropic void, an area of the universe where even the faintest gravitational waves had dissipated, all cosmic energy had disappeared. That’s where I wanted to go.

As I expected Libby had absolutely no interest in the Pluto mission. Her nightmares had stopped and her interest in space along with them. She had if anything a compelling interest in ‘figuring out what’s what’ before she got too old to make sense, and reread everything from Ivan Ilyich to Revelations.

Durer, www.khanacademy.org

Wordsworth was right – while children may have intimations of immortality, for better or worse those glimmerings will never be enough for adults. Meaning or meaninglessness, mortality or immortality, existence for imagination are all to be sorted out before it’s too late. The bad news is that Tolstoy, Sartre, Kierkegaard, and all the rest never were schmart before they were old. There is only so much ‘ratiocination’ that one can take before taking a deep breath and exhaling, “Whatever”, which was exactly Tolstoy’s conclusion (A Memoir) when he backed into faith, only to see his nihilistic doubts return after a few years.

‘Space-Time’ always had a particular meaning for Libby Cullers ever since her nightmares and The Time Machine. She backed into an understanding of a very complex mathematical concept thanks to bad dreams and H.G. Wells. Everybody should be so lucky.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.