Bret Farber had visited Haiti over a period of ten years from the time of Baby Doc until the coup of Prosper Avril, a quiet interregnum when Duvalier’s autocracy kept crime, dissent, and civil unrest in check; when the Tonton Macoutes still were powerful and loyal to the family, and when foreigners could come and go as they pleased in neighborhoods like Carrefour, a sprawling half-city on the outskirts of the capital and on the water, which had the liveliest bars, restaurants and whore houses in the city which now was simply a slum as dangerous and violent as any favela in Rio.

www.wehaitians.com

Bret ate four-star French meals in Petionville, danced until well after midnight at the Fougere Lounge in Carrefour whose dance floor extended out over the water almost to the moorings of the fishing boats and small craft that had come over from Santo Domingo. The rum was always Barbancourt Five Star, the best rum in the world according to aficionados who had tasted the best from Puerto Rico and Nicaragua. The girls were the most beautiful in the Caribbean, or so said the same aficionados; and the meringue bands spelled each other so the music was non-stop and hot.

Only a select few foreigners ever witnessed a voodoo ceremony. Papa Doc had taken the religion very seriously and embraced it as part of his indigenous persona. He wanted it kept unsullied and unpolluted by outsiders. He was glad that guests at the Toulon and the Olaffson could hear the wailings and chants from the hills, but no one was ever allowed up there.

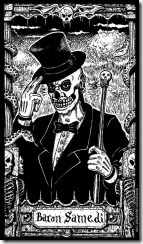

The wealthy mulattoes of Petionville and Kenscoff hated Duvalier, did business with him, and were complicit in all; but still resented the power of this little black, murderous man. Although voodoo had incorporated much Christian ritual – what religion is not derivative? – it was still pagan, uncivilized, and threatening. Which is why Duvalier practiced and promoted it. Believers said he was an incarnation of Baron Samedi, the Prince of the Loa, ruler of the spirit world, and powerful force over the living. Duvalier often affected the tuxedo, top hat, and cigar supposedly worn by the Baron.

Bret made as many trips as possible to Haiti during the Duvalier years, found every excuse to visit, cadged and conned his way to contracts and consultancies, all to be in a place where not only did nothing go wrong but everything went right.

Many frequent travelers describe such feelings as those of kinship. There is something about a city or even a country - atmosphere, rhythm, personality, character, setting – that has a particular and unique resonance; an immediacy. Bret could not disaggregate the many factors which contributed to his sense of cultural familiarity; and in fact wondered why this benighted, corrupt, autocratic state could have such a hold on him.

Perhaps it was the voodoo after all, he thought; the backdrop of all things Haitian, even more pervasive and influential than Brazilian/Dahomey Candomblé, another incarnation of African animism – and far more powerful in expression. Voodoo was more violent, more sinister, more in touch with ordinarily sublimated aggression and primitive passion.

www.telegraph.co.uk

Perhaps it was just elitism – the cocky sense of the well-travelled tourist who ‘finds’ an ‘unspoiled’ place. No doubt there was something to that criticism. Haiti is not for everyone, but an extraordinary discovery for a few.

It might even have been the dark threat of the Duvaliers and their Tonton henchmen. One could never be totally safe, after all, and as the post-Duvalier period showed, the resentment against the family and their autocratic, punishing rule was not far beneath the surface.

www.globalsecurity.org

Whatever the reason, when Bret stepped onto the tarmac, smelled raw fires, frangipani, sewage, and roasting meat, and walked past the Tonton Macoutes smoking on the verandah and watching, he knew that he was home.

It was not surprising, therefore, that Bret met Lauren Chennault, a French Canadian whose background, language, education, and culture were far different from his. She had been born and brought up in Baie-James, at 52 N. Latitude not far from the Artic, Hudson Bay, and the Indian nations of the Northwest Territories. Her village was half-French, half-Cree. Her father had moved up there after years in Southern Quebec, started a general store with his savings, had three children, and never left. He sent Lauren and her two brothers to school in Montreal, and she was the only one not to return to Baie-James. A religious girl, she had studied at a convent school and was invited by one of the sisters to join her for a summer in Haiti where the Church had a Catholic mission.

www.fiveprime.org

She like Bret felt curiously at home in Haiti; and she often wondered how a girl from the sub-Artic, convent-schooled, and very parochial in character, cultural, and outlook, could find kinship in Haiti. Her reasons were not that different from Bret’s but since she had spent most of her life in a very simple, isolated monochrome community; and Port-au-Prince was a circus, a kaleidoscope, an impossibly foreign place, her reactions were even more exaggerated and pronounced.

She and Bret met at the Toulon where her classmates had gone for lunch and a swim. They were all staying at the Church dormitory – a severe and unrestored building on Delmas – and often crossed town to eat lambi creole and swim in the large and, unusual for Haiti, clean pool.

www.thebesthotels.org

He introduced himself and asked if she would like a tour of the hotel. The view of the port and the Kenscoff hills was worth a visit, and he would introduce her to the manager who was a musician and artist. He asked her to have dinner with him in Petionville, and they spent an evening at the Côté Cour, Côté Jardin, a restaurant which specialized in both local Creole and French cuisine.

They had little in common. Bret was from an old pedigreed New England family, a product of boarding school and Harvard, and a resident of Washington, DC; and she was more Cree than French. She had learned how to skin seals, to make sealskin leggings and mukluks, and to trek from the Bay to the interior with Indian friends. Her French was mixed with Cree, and her Catholicism, even after four years with the nuns of St. Mary’s, was a good part Native American animism.

www.bostonguides.com

Yet she was Canadian, European, and French – or at least there were enough recognizable traces of these influences for her to be not completely foreign to Bret – and they were never uneasy in each other’s company.

What brought them together, however, was Haiti. There would have been no lovemaking in his balcony room at the Toulon; no dark night with only the Chinese coil burning to keep away the mosquitoes; no breeze from Kenscoff blowing the wide open windows if it hadn’t been in Haiti. If it hadn’t been for Haiti itself.

There would have been no sexual intimacy without the voodoo drums, without the scent of jasmine growing in the gardens of the estates above the hotel, or without the rancid smell of the port that drifted up from the city in the early morning when the air pressure and the direction of the breeze changed. They danced in Carrefour, spent weekends in cabanas on the beaches of Les Cayes and Macaya, and drove up north to Gonaives and Cap Haitien; but never would have had they met across the mountains in the Dominican Republic. Haiti was their go-between, their matrix, their enabler.

www.travelweekly.com

They never talked about Haiti, Duvalier, the Tontons, or voodoo. They only shared experiences from New Brighton, Lefferts, Harvard, and Spring Valley; or Radisson, Fort George, or Nemiscau. Haiti gave their stories a common context. New Brighton and Fort George would now only be remembered as not Haiti. Not hot, tropical, gingerbread, threatening, ominous, passionate, and violent.

It is not surprising that their love affair continued only as long as they met in Haiti. Neither one ever suggested that they meet in Boston, New York, or Miami; and when her summer internships were over and his last contract delivered, they knew that their affair was over. Their friendship was uniquely, irrevocably Haitian.

Nothing ever came close to Haitian kinship for Bret. Bulgaria came close – perhaps because of the same strange elements of autocratic dictatorship, secret police, old culture, ceremonial religion, and music – but personal relationships there were more formal and structured. They all had a cultural diffidence. Romania was only and simply a place.

Bret was a very lucky man. Few people understand cultural kinship, and even fewer have ever had it. His love affair was with Lauren Chennault and with Haiti.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.