The idea of romantic love is relatively new, dating back to the 14th century. Petrarch’s sonnets to his love, Laura, expressed new sentiments of longing, desire, loss, and emotional beauty. The Age of Chivalry was born, women were no longer considered just mates contracted to produce children and extend the family line. The were now to be revered, sought-after for their charms and allure, and kept for their own sake.

When I utter sighs, in calling out to you,

with the name that Love wrote on my heart,

the sound of its first sweet accents begin

to be heard within the word laudable.

Your regal state, that I next encounter,

doubles my power for the high attempt;

but: ‘Tacit’, the ending cries, ‘since to do her honor

is for other men’s shoulders, not for yours’.

So, whenever one calls out to you,

the voice itself teaches us to Laud, Revere,

you, O, lady worthy of all reverence and honor:

except perhaps that Apollo is disdainful

that mortal tongue can be so presumptuous

as to speak of his eternally green branches.

Romantic love, of course, was popular only among the aristocratic few. Peasants had no time for such impractical notions. For them marriage was an economic contract, and the wife’s role was to work as part of a productive, self-sustaining unit. Her value was based solely on her strength and ability to work; her health, a key factor in her economic longevity and her fertility, and the ability to produce more able hands for family work. Marriages were arranged based on economics, and the value of both husbands and wives was calculated on the basis of ability to provide, produce, and maintain.

As economic conditions improved and fewer families lived on the margins, romantic love became an option. Family status, wealth, and importance were always factors in the selection of marriage partners, but romantic love could coexist within much more accommodating rules. Parents gradually lost their complete authority, and while they could act to arrange possible marriages, their children, infected by Petrarch’s virus, often refused their help.

There are some countries, most notably India, which continue the tradition of arranged marriages even in higher socio-economic groupings. This approach to marriage, very conservative relative to Western Europe and America, has as much to do with religion as history. Traditional Hinduism has stressed the concept of maya or illusion. The world is but a figment of one’s imagination, not to be valued or trusted; and man’s only purpose on earth is to reject its temptation on his path to spiritual enlightenment. From the point of view of history, Indians have observed the contentious marriages, divorces, lawsuits, and endless recriminations of the Western world and concluded that their more practical, approach was still best.

The Apostle Paul was notorious in his views on marriage.

Are you free from a wife? Do not seek a wife…those who marry will experience distress in this life, and I would spare you that (Corinthians 7:27-28)

Of course Paul was not necessarily misogynistic. He understood how difficult marriage was and how hard it was for a man to keep his mind on God when he had a wife to deal with. The notion of celibacy was given a boost thanks to Paul. Since he was speaking in spiritual terms – i.e. ideals rather than practicalities – he ignored the economic necessities of marriage. All well and good, Paul, new Christians in Corinth or Ephesus might have said; but celibacy for us means penury.

“I would spare you that” certainly resonates in the mind of many married people who realize what a fine kettle of fish they have ended up in; and most wish that they were once again footloose and fancy-free. Romantic love fades quickly, and as routine settles in, husbands and wives ask, “Why did I do that?”

A very good question. If marriage has outlived economic necessity – men and women increasingly pull their own weight for and by themselves, and children have become an economic liability rather than a benefit – then why bother?

“I don’t want to die alone”, is often heard. What greater comfort than to expire surrounded by loving family and friends. Yet as Tolstoy wrote in The Death of Ivan Ilyich, that’s exactly what we do. A man’s final moments are between him and his maker, no one else. If anything, the crowd of well-wishers is a distraction for his one, pure, indefinable, and absolute moment.

Fear of solitary, lonely old age is another reason why marriage has persisted. Institutionalized living has not yet caught up with the comforts of home; and although many older people make the transition quite easily, for most it is Purgatory. Better get and stay married, goes the argument, or else you will end up in one of those ‘homes’.

So, what’s love got to do with it? Nothing at all. As marriages age, they become little more than private institutions providing social and emotional support. Easier to rely on a partner with whom one has lived for fifty years than on the vicissitudes of the State.

What to make, then, of romantic pictures of 80-somethings walking on the beach? Do they still love each other after all those years? Mutual dependency is a kind of love after all; and there is every reason to avoid any chance of dissension or disagreement and jeopardize the arrangement. Holding hands is the visible sign of an operational contract.

Younger people value marriage differently. Camaraderie, easy sex, compatible interests, and of course children are foremost in their minds. Yet no one has demanded or enforced marriage to satisfy any of these demands. Why should young people voluntarily withdraw from an expansive life at precisely the age when they can most enjoy it? How have we come to value institutional security over individual quest and personal experience?

Married families are considered the ideal breeding ground for children; and yet the number of children born outside of marriage or to single mothers has increased significantly in recent decades. These alternative families have done quite well, and although neither they nor society as a whole have fully accommodated to the new reality, they are likely to be the norm of the future.

Love is at the heart of Christianity, say believers and and clerics alike. The Gospels and the Johannine Letters in particular focus on God’s love for Man – and by extension, the love that Man should have for him:

And we have known and believed the love that God has for us. God is love, and he who abides in love abides in God, and God in him (1 John 4:16)

Jesus knew that his hour was come that he should depart out of this world unto the Father, having loved his own which were in the world, he loved them unto the end. (Mark 13:1)

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength. (Matthew 5:30)

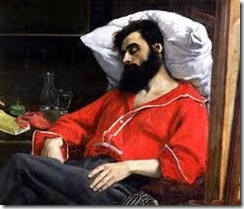

St. Mark www.wikiart.org

Reams of Biblical exegesis have been written on the subject; but one thing is perfectly clear – Love for God and Jesus Christ is as indefinable as any other secular love.

Matthew talks about loving thy neighbor, but the crux of love is divine not secular. The nature of this love and why it is so important is less clear. Why is love of God more important than faith, obedience, and devotion? Why is putting one’s trust fully and absolutely in God less important than loving him?

‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’ (Mark 12:31) has become a scriptural pillar of Christianity. It is less problematic, for it stresses the common secular conviction that there is strength in numbers; that community provides security; and that creating and preserving a respectful glue among community members is essential.

Dostoevsky, writing in The Grand Inquisitor, berates the returned Christ for having perpetuated the suffering of little children. You could have saved mankind from misery, penury, and want; and yet you only offered them the promise of salvation. Ivan goes on to say that this indifference to the suffering of innocent children is unforgiveable.

The love of children is the love of lost innocence. For a short period of a few years, sinful, corrupted adults can be in the presence of unadulterated purity. We don’t love children for what they are but what they represent. Love once again has an indefinable quality – you know it when you feel it.

Moreover, children are luxury goods. They no longer provide for one’s old age, nor contribute to the family income, nor light the funeral pyre; nor represent value in a culture which has devalued ancestral status and privilege; so having them for this brief interlude of innocence can only be characterized as shopping at Saks.

The point is that love is a human construct. Christianity, as a new idea, had to differentiate itself from Judaism – a harsh, legalistic, and spiritless religion in the eyes of those who wrote the gospels – and creating a faith which was based on love, forgiveness, and the promise of a happy, loving afterlife was only logical and sensible as counterpoint.

Romantic Love was equally a construct which thanks to an efflorescence of poetry, a leisure class, and the rejection of dark medievalism, had its day. Generation after generation has had an investment in continuing the tradition, and today’s Hallmark Card culture is no different. Billions are to be made on the idea of romantic love, marriages, and big weddings.

Marriages stay together not because of love but out of social and economic necessity. In a society which more than ever promotes family – a private, privately-funded institution – there is no way that an older couple with modest funds can or will dissolve a marriage.

A reciprocated love between parents and children is the proof of a successfully managed contract.

There is one remote possibility of a real, pure, unalloyed, and unmediated love – that between parents and their children. Because the creation of life is not ordinary, secular, or routine, it has acquired a mystical sense of being. In Biblical terms the ‘one flesh’ of marriage has become an even greater flesh. A child has not simply joined the family club, signed off on rules, regulations, and obligations, and gone about his business as an independent but cooperative member. He has been created; and the ‘love’ a parent has for him is inexpressible.

Abortion, abandonment, disinheritance, estrangement, and abuse suggest that this is nothing but a romantic, idealistic, overly Christian point of view. Procreation say Christian deniers is a feature of the origin and longevity of the species and nothing more. Parental ‘love’ is nothing more than a hardwired emotion to assure the survival of the family’s species.

Disaggregating ‘love’ is almost heresy, for even though we may not understand it, we value it for personal, social, spiritual, and psychological reasons. There has to be at least one ineffable reality in our increasingly secular, technical, and money-driven world. Love has the longest track record, so why not?

Why not indeed. There is no toppling of this particular applecart.

Interesting article. However, I differ with the idea that alternative families styles have done quite well. Over the years I have conducted extensive County wide health need assessments in Ohio. I have found that the single most important determinant of poverty is family type. On average, I have found that sixty three percent of single parent families with a female head of house hold are at or below the poverty level. While among two parent families only downwards of 20% are at or below the poverty level. The traditional two parent family when viewed in terms of economic benefit remains by far the more successful model.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Bill - I agree about the single-family households and correlation with social ills and dysfunction. My point is only that they are becoming more common, they may eventually be the norm as individuals and society accommodate the change. There is nothing to indicate that traditional 'marriage' is permanent, especially, as I have noted, if there are fewer and fewer reasons to justify it

ReplyDelete