Barney Field had always thought of himself as an emotionally stable person,

well-grounded in moral principle, a solid education, and a clear understanding

of himself and the world around him.

His childhood was unremarkable. Barney played by the rules, colored within

the lines, was dutiful and respectful to his parents, served as an altar boy,

did well in school.

Barney himself was only remarkable for his ordinariness and lack of

distinction. This well-behaved and polite little boy, although admired by

teachers and his parents’ friend, was growing up as an emotional and

intellectual cipher. Even Father Brophy hoped to hear a serious sin in the

confessional, but Barney only confessed the most venial ones. In fact, had

confession not been indispensable preparation for Holy Communion and a sacrament

itself, Father would have told Barney not to bother.

Barney’s teenage years were no different. He followed every rule in the

book, continued to be honorable and deferential, treated girls and women with

respect, and never so much as let an elbow rest on the table. By every standard

of the age, he was a model boy, citizen, and member of New Brighton society.

Barney could not remember when the irritability set in; when things did not

seem quite right; when everything began to look off-kilter. Perhaps during the

weekend on Cape Cod where the clambake had gone bad. Nothing he could point to

really, just a feeling of displacement. He had always been taken for granted

and never accorded any interest; but on the beach he was excluded, peripheral,

and insignificant.

At the same time, he began to feel befuddled and adrift. Perhaps he did

belong on the margins. Why, for example, did the most insolent, arrogant, and

posturing boys have such sexual success? Why were rectitude and intelligent

counsel dismissed as irrelevant in sexual affairs? Why was volubility so

attractive? And sports? Why wasn’t his own serious reflection and consideration

of value?

The cracks only widened as he got older. His suspicions of became more

common and more troubling. Perhaps he was a cipher or a dry well. Life could

have no meaning if he had no meaning.

Yet, what might that be? It is very had to construct a personality let alone

character. The genetic dice had been cast and there was no way to re-roll them

until something more advantageous came up. He had to make do.

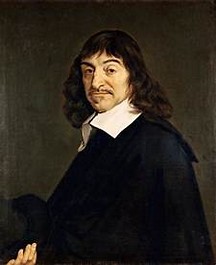

He hoped that Descartes was right. The very fact that Barney had these

doubts about himself signified some existential importance. He must have a

critical, analytical mind and sensitive spirit for them to have even cropped up.

Still, there was no intellectual hook to hang his queries on; no emotional

rivers to follow; no kaleidoscopes to jog his sensibilities; no Borscht Belt nor

no funny bone. No passion, no ambition, no obsession, no nothing.

Whereas everyone else his age was planning for the future – eyeing a mate, a

job opportunity, or an investment offer – he drifted, although not unhappily.

He felt no anxiety about his lack of ambition or vision, only a lassitude which,

if he let himself, felt good.

Although he did not know it, Barney Field was in fact quite unique. He had

inherited genes which are more essential to survival than those of his more

demanding colleagues. He was the raccoon of his species. Not a great hunter or

predator, neither ferocious nor intimidated; but perfectly adaptable to his

surroundings – to any surroundings in fact. Prehensile, nocturnal, cunning, and

opportunistic, the raccoon would certainly be the mammal to survive nuclear

winter.

At college Barney was never concerned that his first choices were taken. A

course on Melville would be just as good as one on Conrad. There would certainly

be plenty of creamed chicken in the cafeteria if he came late. There was always

seating at the polo field.

The cracks sealed themselves once Barney accepted the fact that there was no

there there. Uniqueness was not his specialty, but life under the stream bank

was not so bad either. Life without bother, with no demands for notion or

opinion, and outside the sexual fray was not bad at all.

There is a particularly comfortable zone within the intellectual spectrum,

one in which the individual is not smart enough to obsess over existential

issues but too smart to bungle. The Three Bears Zone’ it was called by a

well-known Czech psychologist. Not many people fell within it, he noted, but

those who did led very content lives.

What Dr. Milos failed to note, however, was the fluidity of the intellectual

spectrum. The individual may rest comfortably well within its confines, but at

times would regress or advance. Sail too close to the edge and become suddenly

and morbidly anxious about death on the one end, or make foolish decisions on

the other.

It was during one of those excursions that Barney first felt

angst.

For no reason that he could tell, he felt nervous, prickly, unsettled, and very

shaky. His backyard looked spotty. The trees were twisted and nasty, and the

birds flew at him. It was too windy for August.

The feeling passed, and Barney went back to his business slightly unsettled

but convinced that it was the ribs or sleeping badly until it happened again,

this time more disassembling and insecure than before. For a moment he couldn’t

remember where he was or even who he was. It wasn’t so much that the garden was

shifting planes and that rabbits and voles were coming out but that he was

deconstructing and shifting planes.

Of course it was a panic attack, and nothing that Barney felt differed from

textbook descriptions. Every attack is unique, Dr. Milos wrote in a paper

written clandestinely in Prague in 1955 – clandestinely because under the

Communists all psychological aberrations were due to the incompleteness of the

Revolution and nothing whatsoever to do with individual, innate disturbances –

and unpredictable in their phenomena. For one person it might be rabbits and

voles, another birds flying backwards, and for a third paralyzing fright.

It is bad enough for a complex person to suffer panic attacks; but far worse

for a very stable, settled, and uncomplicated person like Barney Field. Complex

personalities, particularly the artistically gifted, see the world in unusual

ways. Picasso is a good example of a presumably rational and un-psychotic

personality who saw the world in a scrambled way.

Barney, however, had never seen a teapot as anything other than a teapot and

a perfectly traditionally shaped one at that. White bone china, Victorian

decorations, fluted spout, and slender throat. So when the garden became a

distortion far more radical than Picasso ever saw it, or more weirdly

assorted than Breughel’s, Barney knew that something was seriously wrong.

He was ill-equipped to deal with his increasing anxiety. Such

discombobulation never seemed possible or even imaginable, so he didn’t have the

first idea of what to make of it. He of course had read about psychological

disturbances, but psychosis and schizophrenia were never more than academic

categories; and as far as modern art was concerned, he was ignorant.

All of which is to say that Barney suffered more than those with intimations

of craziness. He was totally, completely, and helplessly unprepared for his

devilish visions.

Dr. Milos had offered no insights into this particular type of psychosis –

i.e. a person with no known history of mental illness, a well-adjusted, loving

childhood, and an adaptable personality which enabled him to cruise the shipping

lanes with ease.

In other words, where did this sudden weirdness come from? Had it been

hidden deep in Barney’s subconscious for all these years? Had the balance among

Id, Ego, and Superego been so perfect that his subterranean demons had been kept

underground? Or was it chemical imbalance the result of some leaky endocrine

valve or bad limbic plumbing?

Milos even hinted at the demonic (for which he had been roundly censured by

his colleagues and the Communists). Why not consider possession, he asked?

In any case Barney went from bad to worse, was only partially salvaged by

psychoactive drugs, interned in a private hospital in Connecticut for short

periods over three years, and then finally committed to an asylum. His only

relatives – an aunt and uncle in Branford – were surprised that such a Victorian

institution still existed let alone in Connecticut; but it was they who signed

the papers.

It was there that Barney Field spent the rest of the days, interrupted from

his daily routines only be squads of research psychologists who wanted to learn

more about how such an ordinary, uncomplicated, and very uninteresting man could

have gone so far off the rails so quickly.

They had no conclusive answers and were as perplexed as Dr. Milos had been

many decades earlier.

There is too little we know of the human genome, suggested one researcher,

and for all we know there are bits of DNA which don’t kick in for many years and

then, for reasons we cannot understand now, drive the individual completely and

irrevocably batty.

“Such cases [like Barney’s] are impossible to explain”, wrote Dr. Milos. One

would hope that ordinariness would have at least one compensation – lack of

anxiety – but it clearly does not. No matter how prosaic and dull one might be,

it is no protection against the insidious infection of madness.”