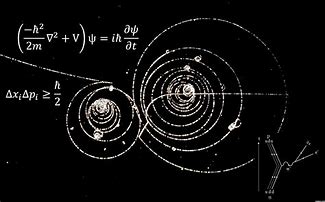

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle, also known as Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties of a particle, known as complementary variables, such as position x and momentum p, can be known simultaneously.

In other words you can’t know where a particle is and how fast

it’s going at the same time. As importantly you can never predict with any

accuracy where that particle will be at any given time, but only suggest the

probability of its being there.

Quantum mechanics was not only a revolutionary mathematical

theorem but a philosophical one. For centuries scientists and mathematicians

assumed certainty. Things were or they weren’t, nothing in between, vague,

imprecise, and uncertain. Mathematical and physical problems might be difficult

to solve, but once they were, they would remain fixed and explicit until they

were successfully challenged.

Even philosophers questioned the nature of things – Bishop

Berkeley wondered whether a falling tree would make a noise if there was no one

in the woods to hear it. Einstein postulated that an astronaut travelling at

near the speed of sound would age less than those he left behind. There was

something peculiar about time, he said, that did not follow human perceptions

and laws.

If Einstein was right, might there be a way to slow time so that

we might have more of it? Or as Berkeley suggested, might there be more than one

perceptual worlds?

In both cases, no matter how intriguing the theory or the

subsequent questions, the ideas were solid. One may never know or experience

the slowing of time, but one day it would be proven. Similarly, there may be

such a thing as concomitant reality – two worlds, one unpopulated and the

other populated but both available to one observer simultaneously.

Max Planck, Heisenberg and others when devising the discipline of

quantum mechanics dealt with a very different and perplexing reality – a

probable, uncertain one. Until or unless an new, revolutionary theory is

discovered, we will have to assume that our logical, rational, practical laws of

assumed existence do not apply in the particle world. And if they do not exist

there, in what other spheres of existence might they be displaced

by uncertainty?

Probability of course is nothing new. We never know for sure

whether it is going to rain or not in ten days; or whether the stock market will

go up or down; but we can assess risk and probability and make an educated

guess. In fact most decisions are based on uncertainty; and other than the most

obvious fixed, absolute things – sinks, dogs, or water – we live in a

probabilistic world.

Yet this is still nothing like the uncertainty of quantum physics

where it is impossible to determine exactly where a particle will be.

Eventually weather forecasting will be so accurate that we will know far in

advance about every climatic event; but we will never be able to pinpoint the

location of a particle travelling at a given speed.

Since quantum physics is a mathematical fact; and since its

application to other physical events is not beyond the realm of possibility; and

since normal, everyday life is necessarily one of probability and uncertainty;

then why should anyone care about pinpointing anything? Why does the question

‘Who am I’ persist even though we are composed of billions of bits of DNA

material acquired over millennia from unknown ancestors which has been twisted,

configured, and formulated again and again each time one’s genome gets mixed up

with someone else’s?

Men and women of questionable or indeterminate sex are

not left alone with their uncertainty, but either asked to choose one binary

option or the other; or most recently to subscribe to a new category –

transgender. Sexual uncertainty is not an option, despite the fact that given

the fundamentally uncertain nature of human existence, it might well be.

It is quite human and natural to want to fix things in place, to

configure them according to familiar, prescribed categories, and to present a

cogent, coherent unity. Things are much easier that way.

Everything we do is contingent upon something else. Napoleon,

suggested Tolstoy, lost the crucial Battle of Borodino not because of failing

mettle but because of a cold which had been brought on by wet feet in turn

caused by the failure of his valet to bring his gumboots to the battlefield.

We are not only simply a collection of randomly configured DNA but

of random events which occurred in the recent and distant past. There is the

possibility that enough of Great-great grandfather Hiram’s genetic bits showed

up in one of his descendants and they turned out to be the same profligate

wastrel that he was. Who would know? And who could predict?

To be sure image and identity serve a useful purpose. If there

were no titles, genealogical history, performance markers, behavioral traits

that told our story to others, everyone would be confused. It is not that

identity is not important; it is that it is not existentially important.

By focusing to such an exaggerated degree on personal identity, we

lose the most essential human characteristic – dynamism. While we are most

certainly programmed by nature and nurture, there is nothing that enslaves us to

either one. In fact, a life of deliberate uncertainty – about God and the

nature of religion, metaphysics, epistemology, sexuality, social exchange and

structure – may be the most fulfilled.

For Nietzsche and Schopenhauer the individual and the expression

of his pure will was the ideal form of existential reality in a meaningless

world; and in some way their theories touched on the principles of uncertainty.

Yet they called for a very certain, distinct, and unmistakably unique,

determined, willful individual.

Personal uncertainty goes beyond nihilism and determinism, for the

‘uncertain’ individual never searches for identity, individuality, or

personhood. He is quite happy with the cards he has been dealt, the vagaries of

the probabilistic environment in which he lives, and sees no need to waste time,

energy, or emotion on figuring out what’s what.

Today’s society is obsessed with identity – sexual, philosophical,

social, and personal. It is unconscionable for

anyone to demur or even refuse the categorization, the first step to

mobilization, civic action, and change. In fact, in order for

things to change, they have to be themselves identified, categorized, and marked

for intervention. There can be no uncertainty in the revolution.

Markers are everywhere – LGBT, conservative, liberal,

environmentalist, fundamentalist, traditional, entrepreneurial, exploitative.

More conservative Americans who have never had any belief in

either progress, idealism, or a better world and who have relied on history for

guidance, are indifferent about these charges against Trump. They see no

problem with his eccentricity, vagaries, or inconsistencies. They – and life –

are like that.

Most of us desperately want something to hang on to and are

uncomfortable with anything shaky, precarious, or uncertain. We want things in

their place day after day, absolutely fixed and as unchangeable as possible. We

are afraid of both the dark and what’s around the corner.

A few of us are unconcerned about ‘fixation’ and are happy to

give in to our jumbled, garbled, and often incoherent ways. We don’t care who

we are, what we represent, or how we fit in. We are neither Nietzschean

supermen nor Napoleonic geniuses; but are quite content with our uncertainty and

that of everything else.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.