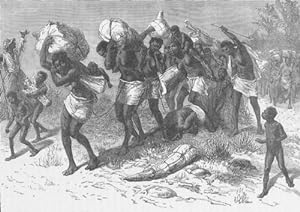

Absalom, Absalom is William Faulkner’s finest work, certainly the greatest work of American literature, and comparable to Joyce in complexity, virtuosity of style and language, and story. Absalom is the story of Thomas Sutpen, and the creation of Sutpen’s One Hundred, a Mississippi plantation cut from 100 square miles of impenetrable, swampy undergrowth by his ‘wild Negroes’, a band of African slaves bought from Caribbean slavers; the building of his mansion by them according to the designs of a fey French architect; the tale of his many lovers, relatives, and children; and the tragic endings of all.

Absalom, despite its literary genius, is a melodrama at heart. Thomas Sutpen has a child, Charles Bon, born of a New Orleans octoroon mistress, both of whom he abandons until the illegitimate son comes back in to his life to propose to his legitimate daughter, and is murdered by his legitimate son who is in love both with his half-brother and his sister.

Sutpen, in addition to his two legitimate children and Charles Bon, has another daughter, Clytie, whose mother was black, quadroon, or octoroon, but of mixed blood and of mysterious origins; and a fourth child, the daughter of his overseer who is murdered by her grandfather in another expression of racial hatred and hatred for the predatory Sutpen.

Charles Bon, paralleling the life of his father, has his own son by an octoroon mistress, a young man who, after Bon’s murder, comes back into the lives of the remaining Sutpens. Sutpen’s wife’s aunt, Rosa Coldfield, harboring resentment and hatred of him because of his unsavory past and questionable parentage and origins, and his diffident treatment of his wife, becomes the caretaker of her niece who is ‘widowed’ because of her brother’s murder of her fiancé, Charles Bon.

After her sister’s death, and the increasing remoteness and isolation of her niece, Rosa agrees to marry the hated Thomas Sutpen – an act of self-abnegation, –recrimination, and defiance.

The story of the Sutpens is as melodramatic as the early plays of Eugene O’Neill. Mourning Becomes Electra is also the story of a family patriarch, an embittered, jealous, adulterous, and murderous wife; complicit, violent children and the complicated and theatrical relationships among them.

O’Neill’s work, however, rarely rises above melodrama, while Faulkner’s impossibly complex and destructive relationships are necessary to tell the story of the South, its racial complexity, and of an entrepreneurial, individualistic, and heroic America.

Race, bloodlines, intricate family substrata, and the dynamics of jealousy, ambition, and incest are all at play in Absalom. Generations hence, it would be difficult for the descendants of this genetic potpourri to determine exactly who they were, to whom they were related, and where they came from. Today’s ethnic and racial diversity is simple and straightforward by comparison.

All black people can trace their ancestry back to Africa, but as in Absalom there was little racial propriety. Slaveowners were just as likely to father children by their slaves as Sutpen was to have mixed blood offspring. It is the extravagant excesses of the characters in Faulkner’s work which make it far more interesting than anything within today’s diversity.

The calculus of racial divisions in Sutpen’s day and the importance of fractional racial differences – half-black, quadroon, octoroon, or one-sixteenth black codified in New Orleans – made ascription difficult the farther removed generations were from the first miscegenation.

Through ancestral history and DNA testing, a black man may find out his fractional whiteness and African region of origin, but the isolating forces of slavery, while easily ignored by sexually predatory white plantation owners, were enough to ensure black-on-black mating. The black man may never know who his great-ancestors were, given the sexual freedom encouraged by slaveowners, only his African provenance and intermittent and faded family recollections.

Black men and women who want to explore their ancestry are blocked early and often. Slaves were property, and as such recorded in ledgers, not historical documents. The parentage of children by white overseers or grandees was known, but ignored.

Bob Moffett was a white, patrician American, brought up in New England, the descendant of America’s earliest European settlers, both Northern and Southern. His lineage was easily traceable back to the first English settlements in Boston and Salem and to Jamestown. His American heritage was impeccable. Both mother and father on both sides of their family trees were of storied stock, and Bob’s family was rightly proud of their heritage.

This, however was not enough for Bob since he suspected that at least the Southern half of the family had to have been slave owners, had to have had children by their slaves, and therefore been the worst of the worst. Not only did they have slaves, but they sexually abused them, fathered children they ignored and even sold them downriver. Bob was afraid of what he might find, but felt that he had to leave no stone unturned.

Bob was a leading member of the progressive movement in America, had been on the busses to Selma and Montgomery, marched in unison with black Mississippians, and sat in with them at segregated lunch counters. When the racial civil rights movement began to fade, Bob quickly joined Women’s Liberation and marched with his sisters to protest the glass ceiling, and angrily fight against male dominance and patriarchy.

Once women succeeded in making significant strides on their own into politics and business, Bob found allies in Gay Pride. He was once again in the streets, at the barricades, and very visible in the Castro, Bay-to-Breakers, and Folsom Street. Finally, and once gays had found their own momentum, Bob moved to Climate Change; and was as active in protesting the predatory, exploitative actions of big business.

So discovering an unsavory racial past was not just any ancestral find, and he wondered how he would explain a flawed racial past to his black brothers and sisters.

Not surprisingly, he found that both sides of his mother’s Southern family were slaveowners. They had operated large tobacco plantations in Virginia and North Carolina and then, like the fictional Thomas Sutpen, made their way to the Mississippi Delta to clear land and grow cotton.

The family, of course, made no attempt to hide their prosperous past, and in fact were well known among plantation society as some of the most prosperous and influential. Some of their elegant plantation homes still stand, and have been placed on the National Registry. They did not just own slaves, but they had owned hundreds of them to work the thousands of acres of cotton. Their slave-owning past could not be ignored.

To Bob’s surprise, however, the Northern side of his family had as nefarious a slaving past as the Southern. The Moffetts for a hundred years lived in New Bedford and were shipowners active in the Three-Cornered Trade that shipped rum and goods to Africa, slaves to the Caribbean to work the cane fields, and sugar (to make rum) to New England.

The Moffetts made a fortune out of the trade and had become prominent in New England society, enterprise, and government.

Bob was all ready to confess, to offer abject apologies for his families’ sins, and to ask forgiveness from his black and white progressive colleagues and friends. Although he had done more than his share to expiate a priori any taints of racism in his past, it would never be enough. The fact that racism was a part of his heritage, his bloodline, and his DNA was enough for him to prostrate himself before all.

Yet the real surprise was yet to come. Bob’s DNA test showed that he had far more black blood in his veins than he ever suspected. His Southern ancestors, it turned out, were, perhaps because of their power, influence and large slave-holdings, more sexually active with their slaves than most other privileged whites of the era. Not only that, his Northern ancestors on their stopovers in the Caribbean, had had numerous sexual relations with the slaves in the colonies. His DNA could be traced back to the regions of origin of both the American South and the Caribbean – Angola for the former and Sierra Leone for the latter.

While such identification is never perfect and not yet perfected – many slaves from the Caribbean were imported to Virginia in the early days of slavery rather than from Africa – the clues are there, and Bob took them to heart.

He was a black man! He was now authentic, the real goods, bona fide. All the nasty bits of his slave-owning past would be ignored, forgotten, and dismissed in the light of his blackness. Of course those who lionized Bob because of this were quick to overlook the nature of Bob’s black heritage (the incidental mating of slaveowners with slaves). It was blackness, color, African brotherhood which counted.

By this time in his career, however, life, progressivism, and black civil rights had moved on – they were younger, more demanding, more violent, and more black-only. Black Lives Matter turned down his overtures despite his protests and blandishments. As far as BLM was concerned he was white, privileged, and useless.

Hurt, denied, and disillusioned, he reluctantly retired completely from his progressive causes. Blackness he thought would give him legitimacy in all progressive causes as he listened to ‘Global Warming and the Plight of the Black Man’ given by a former colleague of his at Duke. He was right in principle, but wrong on human nature. He was too old, too white, and too visibly patrician (statues to many different Moffetts were all over Boston, New Bedford, and Gloucester; and to the Southern Carters throughout the Tidewater and south).

The last anyone had hears of Bob Moffett, he was living in an assisted living community in Gaithersburg. No one there could have made any sense of his ramblings about Martin Luther King, Africa, or the Castro even if he had spoken clearly and logically; but dementia being what it is, he confounded Sierra Leone with the Sierra Nevada, the Castro with Castro, and the glass ceiling with glass bottom boats. He told stories about climbing California mountains, paddling in the Everglades, and movies about Che and Fidel, and was angered when his roommates never got his drift.

Leave well enough alone is perhaps Bob’s legacy. He ended up as a supernumerary in the Progressive Movement, an afterthought if any thought at all, nodding off at the Wellspring Senior Living Center, eating his Pablum and getting his diaper changed, happy enough to not remember why he was there.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.