Tuba Büyüküstün is a Turkish actress of remarkable beauty well-known for her work on the television series, Kara Para Aşk

Despite the claim to the contrary, beauty is not in the eye of the beholder, and even those who may prefer a woman of less classic, dark looks and more sensuously alluring (Marilyn Monroe), will agree that Büyüküstün is beautiful. Her type of beauty, with predictable cultural variations over time, is reflective of those characteristics which have always made women attractive. Symmetrical features, luminescent eyes, full lips, and luxuriant hair all express health, wealth, and well-being as well as being pleasing to a natural sense of geometrical order (the golden mean is universally appealing), and sexual appeal. There is little difference between the women painted by Leonardo and Tuba Büyüküstün.

Asian women are no different and film and television actresses have the same classic beauty as their European counterparts.

While internationalization must be factored in – an appeal to the mean rather than respect for more insular, traditional cultural beauty - the same rules apply.

Since most women are not beautiful, sayings like ‘Beauty Is As Beauty Does’ or ‘Beauty Is Only Skin Deep’ reflect a cultural compromise. It is within that one should look for beauty; for the intelligence, compassion, consideration, talent, warmth, humor, and energy that are far more important than superficial looks.

Feminism was particularly significant because it attempted to redefine beauty and change perspective from a purely male one to a female one. What men thought of women was irrelevant, said feminists. Every woman’s ‘beauty’ was relative to her and her alone; and that female value and worth had nothing whatsoever to do with looks or appearance.

This new perspective was indeed radical because it challenged the notion of essential beauty and challenged men’s authority at the same time. It was appealing to women not only because it gave them new authority, esteem, and privilege but because it marginalized the idea of physical beauty.

Or so feminists thought. Women today might be more self-aware, confident, ambitious, and powerful than ever before; but classic beauty has not lost either its appeal or place in popular culture.

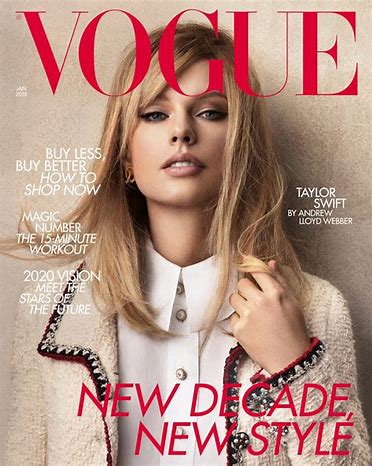

Women’s magazines all promote the same classical beauty of days and eras past, and the message is clear – this is what you are supposed to look like. The influence of multiculturalism is evident, but the p principle features of feminine beauty remain the same.

More importantly this universal standard of beauty suggests the obvious but often denied fact that women dress for men. Despite the revolutionary changes in the roles, responsibilities, and status of women, they still understand that physical beauty classically defined, is helpful if not necessary for attracting mates. The more beautiful the woman, the greater likelihood that she will attract an equally attractive man who, like them, is likely to be healthy, wealthy, and successful.

Study after study have shown that beauty has benefits far beyond the bedroom. Attractive women and men are given preference in hiring. While supervisors may not admit it, a candidate with all the professional qualifications plus beauty, is more likely to get the job. Professor Shahani-Denning of Hofstra University has compiled the most important research on the subject.

The bias in favor of physically attractive people is robust, with attractive people being perceived as more sociable, happier and more successful than unattractive people (Dion, Berscheid & Walster, 1972; Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani & Longo, 1991; Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986; Watkins & Johnston, 2000). Attractiveness biases have been demonstrated in such different areas as teacher judgments of students (Clifford & Walster, 1973), voter preferences for political candidates (Efran & Patterson, 1974) and jury judgments in simulated trials (Efran, 1974).

Recently, Smith, McIntosh and Bazzini (1999) investigated the “beauty is goodness” stereotype in U.S. films and found that attractive characters were portrayed more favorably than unattractive characters on multiple dimensions across a random sample drawn from five decades of top grossing films. The authors also found that participants watching a biased film (level of beauty and gender stereotyping) subsequently showed greater favoritism toward an attractive graduate school candidate than participants watching a less biased film. In the area of employment decision making, attractiveness also influences interviewers’ judgments of job applicants (Watkins & Johnston, 2000).

It is not surprising, therefore, that billions of dollars are spent on women’s cosmetics alone (an estimated $62 billion in 2016) and many billions more on clothes and apparel. If one is not born with natural beauty, there are many ways to compensate. Cosmetics which accentuate naturally attractive features and disguise the unattractive; or clothes which complement skin color, natural line, and physical attributes will always be in demand. Beauty is big business, and with the weight of social history and biological imperative behind it, high revenues should be no surprise.

Diana Vreeland is perhaps the best example of how clothes, cosmetics, and hair style can compensate for unattractive physical characteristics. In her autobiography, D.V., she recounts her particularly difficult childhood years, a very unattractive child with a beautiful sister. Although she attributes her success to talent, perceptiveness, and artistic ingenuity, she does not deny the influence of her early life. Vreeland, never an attractive woman, went on to become the doyenne of fashion as editor-in-chief of Vogue and a long tenure and Harpers Bazaar. She believed that not only were clothes important and could compensate for a lack of classical beauty; but that they added value. She promoted the idea of style – an attitude more than a look not dissimilar from the Italian bella figura but far more dramatic. Vreeland was never a beautiful woman, but no one noticed.

Vreeland never dismissed the essential principles of beauty – the woman in the photograph above is as classically beautiful as Tuba Büyüküstün or the woman in Leonardo’s painting – but suggested that style was not only appropriate but essential for all women.

Only during the decade of The Sixties did beauty go underground. In defiance of everything traditional and conservative, hippies rejected the notion of physical attractiveness as a bourgeois sentiment. Hippies were defiantly unattractive. Of course style never completely disappeared. Beautiful women with disheveled hair and dirty jeans were still beautiful, still preferred, and still attractive; only the elements of style had changed.

Many actresses like Helen Mirren have kept their beauty, style, and allure well into their 70s. It is all well and good to say that beauty fades and that belief in inner qualities is justified; but Mirren defies that notion. She is not only a gifted, supremely talented, intelligent actor, but a beautiful woman. Her performances would be enough to assure her following; but she insists on looking good, a thing of beauty far beyond the fading blush on the bloom of a rose.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.