Burton Ellis was to most an ordinary man with an ordinary wife - a good man; not a model husband but not an indifferent one either; an acceptable father, a decent member of society, and a hard worker. To the surprise of everyone, he dropped dead suddenly. He had led a good, long life, everyone said, and they thanked the Lord that he had been taken off quickly and painlessly.

On and on they droned, he was the brave captain of every ship he sailed, friend of rich and poor alike, a leader, an eight-handicap golfer, a prankster, and a bowler. By the end of the ceremony he was a dreary dud.

The real person, that intimate, cross, contrary soul that Burton was could not be revealed. Funerals are points of reference. He lived a good life, he died, he will be missed. There should be nothing more to say, no details needed, no embellishment.

Burton Ellis was by no means an ordinary man, nor a particularly good one. He could be scratchy, mean, and indifferent. He had lost more friends than he gained. He could be nasty, impatient, and arrogant but these sharp edges were 'fool foils'. There was no room for complaisance or cheap novels in his life. He lived on a wing and a prayer, escaping capture by the skin of his teeth - a morally fungible soul as adaptable as a raccoon, able to skim the surface of cultures, women, and ideas without deeper entanglement.

He was a political contrarian of no particular party, an atheist, and an Adam Smith laissez-faire economist, an objective examiner of the Old South, a student of the economics of slavery, and a monarchist - all of which could not possibly be mentioned in his eulogies.

He was 'a friend of the poor' reflected a former colleague who knew Burton in Ouagadougou together on a World Bank mission to revitalize the sagging health system; but Burton had quickly seen the endemic corruption of the Burkina government and the total impossibility of any reform, and spent his three weeks in-country drinking beer around the pool of the Independence with Burkinabe intellectuals and actresses from Hollywood-in-the Desert, the up-and-coming West African art film industry.

He was desultory in his work because of the indifference of his government counterparts, more often than not busy with tribal business and mulatto paramours, 'out of station' or 'otherwise occupied', and thanks to a silver tongue and golden pen he was able to speak and write his way into a return contract which he accepted without hesitation.

The Bank colleague, however, spoke only of Burton's professional elegance, his canny understanding of foreign cultures, and his contributions to end world poverty.

Another speaker spoke of his congeniality and social graces. "Everyone loved Burton", he said; but the real Burton was tolerated by most, loved by a very few, and rejected by many more. His brand of sharp satire and unvarnished irony put most people off. Rather than tell the truth to the congregation - his intelligence was unmatched, his intellect provided the fuel, and his personality the fire - the speaker chose to round the edges until Burton became anyone, any man, transparent - a cipher.

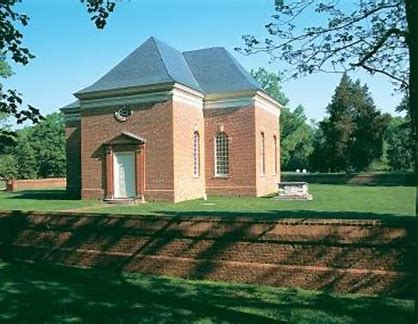

Better to be cremated unceremoniously, a bit of smoke and ash, and memories for those who actually loved him, appreciated him, and missed him. A plot in the graveyard of Christ Church, the oldest church on the Northern Neck of Virginia, Anglican, spiritual home of English colonists and after disestablishment, new Americans is to be his resting place, proper and fitting for an admirer of old ways and passionate about them. He will be in good company - Virginia colonial governors, clerics, and landowners - all wanting a peaceful place of rest in church grounds which will remain unchanged for another two centuries.

So why was Burton's life best described by the platitudes spoken at his funeral? Was it because he had no track record to speak of, no paper trail, no trophies or gold watches, nothing to point to, 'I did that'; only a prickly, scratchiness that kept most people at a distance, but when soothed, had moments of peculiar insight? Appreciated by his daughter who would have him no other way, and certainly not like the other fathers of the neighborhood who settled in and never budged; who were content with complaisance; and who never stole any fruit from the neighbors' trees.

He was an eye-painter, a moral troubadour, a social brigand, a moral adventurer, a bad boy. He had no causes, no ladders to climb, and no regrets. A complete man, as it were, without deliberate compartments. He fit no category, no filing system. And it was because of all this that he was envied b the doers who limned his praises at his funeral. He was the one who got the girl.

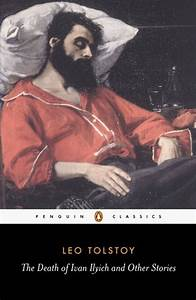

Tolstoy in his novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, observed that we all die alone; that the composite of a random life is worth nothing more than the pieces of a broken mirror. It is to the finality of the next step that one should turn, not to the relatively petty concerns of the past; so it is with some bemusement that the spirit of Burton Ellis heard the platitudes eulogizing him. Had he seemed that simpleminded? That ordinary? Was he so predictable to those who eulogized him?

Not that it mattered, for as Ivan Ilyich said in his final words, "Death is finished". A conclusion to a life neither satisfactory nor unsatisfactory; neither satisfied nor unsatisfied, but life.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.