Amanda Longworth grew up in a small town in the Midwest, and never left the prairie until she was seventeen and a graduate of Baldwin College. Baldwin had been one of the first schools in Iowa to accept women, a promise made and kept by the Reverend Jacob S. Pickens who had been raised by two loving aunts, an older sister, and a grandmother.

His uncles worried that the boy would become a sissy, what with all this woman-handling, but everything turned out just fine. Jacob had Sassy Martin in the woodshed at thirteen and a variety of chocolate- and coffee-colored quadroons at Mme. Landry’s Palace of Earthly Delights on Bourbon Street not many years later.

Shortly after returning to Iowa after one of his many sojourns in the Quarter and after a particularly steamy night with Blanche de Castille, la crème de la crème of Mme. Landry’s establishment and as a result with a newly appreciative understanding of women’s vast, imponderable beauty, he opened the doors of Baldwin to two serious young women, one the grandaunt of Amanda Longworth.

Of course given the tenor of the times education had made these young women even less marriageable than they had been before, and although the doors of Baldwin were now open to intelligent women, the farmhouse was still not. Quoting Shelley (a favorite of Reverend Pickens who had read his verses to Fanny LaCroix amidst paper flowers and scent on a four-poster Mallard bed) was prima facie evidence of an unsuitable wife; and the two matriculates ended up sour old maids.

After graduation from Baldwin,

Amanda found that her newfound love for learning and especially for the Romantic

poets, a legacy of the Rev. Pickens and his New Orleans epiphany, didn’t get

her very far in feed stores, granaries, tractor outlets, and large animal

veterinaries. Onomatopoeia, iambic

pentameter, and metaphor were frilly women’s things in a man’s world of

overalls and gum boots, and after a year of notions and incidentals, she left

Barker’s Variety for France on a church-sponsored tour of ‘enlightenment,

faith, and culture’.

The young woman was transformed by the experience; and after only a day in the city, the drab, grey, and dismal reaches of the prairie were forgotten, lost in a whirl of fashionable women, elegant men, and a culture of easy sophistication. Far from the centerpieces of the tour they were supposed to be, Notre Dame, St. Sulpice and St. Eustache were but distracting obligations. The city itself was the main attraction – the cultural Northern Lights, an epicenter of romance. No book by Fitzgerald or Hemingway could have prepared her for such a vision – there was not only life beyond the prairie, but a sophisticated, desirable world of impossible probability.

Little did she know that what was for her an event of some proportion was the common dream of millions of women caught in the same track of predictability – women plowing, furrowing, seeding, and gathering with little hope of escaping the dreariness and boredom of married life. For respite, these women had only romantic novels which they bought by the pound and read after the cows were milked, the chickens fed, the table cleared, and the men were out in the fields. Theirs was a dismal, forgotten lot, marked only for birthing, obedience, and routine, dogged sex. They had never been aroused by their humping, dull, and plodding mates; never been courted, charmed, or pursued.

Amanda Longworth was the very image of the entrepreneurial American, touched by an idea, sensing the tenor of the times and the market, attuned to collective desire, and aware of the disposable income to satisfy it. She would take these women to Europe and beyond, to the Taj Mahal, Luxor, the Coliseum, and the Black Forest. Travel would be an elixir, an existential tonic. In her hands Paris would be an affair not a destination.

There would be no confounding, irritating churches to remind the women of duty and responsibility; no ponderous studies of history. Kings and courtiers would be seen dancing the minuet. There would be no wars, palace coups, doctrinal secession, or incestuous ambition. Amanda’s remaking of the past would be consistently romantic, beautiful, and attainable.

Travel for Americans has always been an escape from the dreariness of a life of low-brow ambition. America, for all its economic power and international influence is still a cultural rube. It never had a Louis XIV, no Imperial Russia, no majesty, courtliness, or manners. It was a dull if prolific place.

Taking a cruise up the Rhine or down the Dnieper with stops at chateaux, palaces, and country estates was more than just exploration. It was an expedition to imagined places, a confirmation of fantasy, the assurance that there really was a world beyond Bethpage or Dubuque, and a better one.

Even with Amanda’s magical sleight of hand, her meticulous planning, and cultural insights, her tours would never have been the emotional releases she had planned them to be without Americans’ love of what could never be but which still might be. Tourists who travelled to see the Blue Mosque, the Alhambra, Chartres, The Winter Palace, or the Palace of Versailles photographed them, archived them, and soon forgot them. They had never become incorporated, organic or relevant. Incidental expenditures, trophies that everyone has, fragments embedded in the memories of missed connections and disappointing food. Amanda's tours would be different, sexually alluring, and personally satisfying.

Tourism was both an ambition and a

satisfaction – a dual prize for the shut-in.

The image of Notre Dame, as familiar as the Mona Lisa, had already worked

its magic. It had to be better and more

spiritually exciting than imagined because it was always there alongside

conjugation and vocabulary in French I grammars. The illusion had already taken hold by the time

the tourist stood in front of the real church.

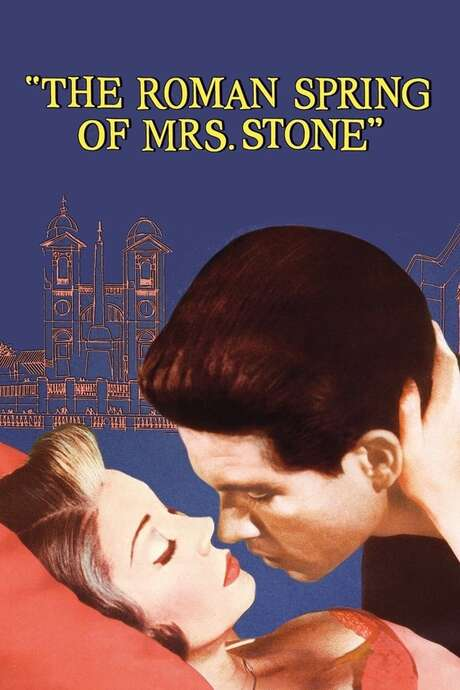

How Amanda satisfied these unhappy housewives was a mystery, a work of alchemy and secrecy. Was The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone a real possibility? Was sex in the 7th or the Bois de Boulogne a reality? Was Amanda simply an international madam with a canny intimacy with the inner life of her clients?

Tourism alone could never have been so successful. It is nothing but a predictable, tedious, repetition of docents and obligatory stations; an itinerary easy to remember and easier to recall. Painful hours in front of altars, icons, statues, and oils, all out of context, memorialized only because of their currency, otherwise ciphers.

Amanda’s tours would simply have to be more satisfying and more revealing about tourists than sights, something between Mme. Landry's boudoir and the Count de Valmont - an escort service individualized to suit the shy, the tentative, and the hungry. A no-questions-asked sexual liaison with no consequences except unforgettable memories of pleasure. A weeklong tryst in the gardens of Versailles, the Tuileries, and in the dining rooms of the Grands Magasins. To be squired if not bedded, to be treated royally if not by royalty; to be a woman again.

It was all thanks to the Reverend Pickens and his love of Romantic poetry. Without Keats and Shelley to stir up the sexual embers in Amanda Longworth and give her ideas, she might be only be a tour guide to the Washington monuments.