Betty Walsh had struggled with her weight since she was seven, a tubby little girl with ringlets and a cute smile who loved cookies and cake, double dark chocolate ice cream (with jimmies, a cherry, and whipped cream on top), stuffed extra packs of goldfish and cheesy things in her lunch box, couldn't wait for school to be out so she could have a delicious strawberry jam-filled crepe with chocolate sauce and creme fraiche, and just loved her mother's Philadelphia Irish mashed potatoes, dripping with butter and the delightful bits from the fatty nooks and crannies of yummy thick pork chops and gravy.

Her mother was an ample woman, sweet Annie O'Grady, plump and delectable, ogled by the altar boys who served at Father Brophy's mass and held the paten steady while the old priest trembled and shook and gave communion to Bridget Connell and her sisters next to the widow O'Bannon and Henry Figgins who, drunk as he always was, managed a quick confession, absolution, and presence at the last mass of the day.

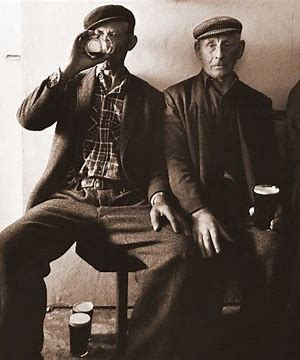

Annie O'Grady married the butcher's son, Sean, and cooked the tail end of the best cuts sold to her husband's customers on the Main Line who came in to South hilly for a bit of taste and smell of the Old Country which their ancestors had ruled for centuries. Walsh's Butchery was the place for the finest meats, the best service, and a homey atmosphere.

Betty helped out at the butchery on weekends and after school, proudly wearing a mini-apron, properly bloodied from the chopping block in the back room where her father neatly sliced ribs, chops, and loins.

Dinners were always a family affair, a big, sumptuous meal of potatoes, chops, gravy, and a fruit pie and ice cream for dessert. Her father was a good provider, the family wanted for nothing, and she was a cute, healthy, rotund, and happy child

She could never stop marveling at the mysteries of food - bloody hanks of steer turned into delicious, marbled, charred steaks; rancid, nasty-smelling sheep miraculously served on the table as leg of mutton with mint jelly and fixings; the occasional rabbit or goose for Christmas; the innards, the offal, all the tasty pungent bits from the animals from the North Philly stockyards.

When she was twelve, the family moved out of lace-curtain South Philadelphia and its doilies, rosaries, and scented toilet water to the suburbs, not the Main Line but an approximation, across the line in Delaware to a properly up-and-coming mixed neighborhood - mixed in the mid-century sense, not today's with colored and Puerto Rican. The Walshes were prosperous, and the casseroles, joints, cruets, and pots-au-feu of the newly assimilated family displayed wealth and well-being.

All of which is to say that the growing girth of little Betty was celebrated. Her baby rolls, pudgy thighs, and ample belly were markers of the family's worth; and so she ate like a queen, everything offered, nothing denied, and on her fifteenth birthday, her Irish quinceanera, the day was celebrated with spice cakes with cinnamon frosting, great dips of vanilla raisin ice cream, hot fudge sauce, and nougat candies.

It wasn't until her first year at T.S. Woodson high school that she heard whispered 'fatty', 'gross', 'bulbous', 'cow', and 'little piggy' directed at her. In one fell swoop she went from adored little marvel to fat girl, plus sizes, and left-on-the-curb social orphan.

'Celebrate your particular beauty', advised her advisors, thin as a rail but committed to diversity and inclusivity which meant the likes of overweight, indulged, conservative patsies like Betty. Social brown shirts, sentinels in the halls and on the playground to call out and arrest naysayers, rude, uncultured fat-insensitive laddies tried their best to smother insult and injury at Betty's expense, but to no avail. She was and always would be, The Fat Girl.

And so it was that she joined The Club - those designated as Protected Species who were collected, rounded up, and put in social zoos. She joined Bobby Porter, as dumb as a stone, clueless, unteachable, dopey, and stupid as they come; Hansel Fried, twitchy water boy and equipment manager for the Woodson Spartans; and Isaac Bernstein, piano prodigy but dorky geek that nobody wanted. These students were celebrated, pulled up on stage to inaugurate, introduce, and applaud the cool kids in a fireworks display of diversity, but who went back to their cages to be gawked at and laughed at as stone creeps.

Much to her surprise Betty was repeatedly selected for prominence. 'You', said the chaplain and ex-officio spokesman for the the marginalized at Woodson, 'are among the best and the brightest', and so should show the world how 'The Other' operates. Her appearance at graduation feting the valedictorian would be seminal, meaningful even more than the achievements of the top scholar.

And so it was that Fat Betty stood before the hall of celebrants, mothers and fathers of graduates soon to be somebodies, rolls of fat shaking as she walked to the podium, cases of fat squeezing her cute little Irish mouth, Irish eyes pinched and crabbed by a fatty neck and thick forehead

"I am here to thank you", she began, reading from a vetted, prepared speech, "on behalf of the entire Woodson community". Here she paused and gestured to Rolf Jansen, locked tight in a wheelchair; Marcie Talbot, blind as a bat, Oberlin matriculate, President of the class; and La Pharaoh Washington, summa inter pares minority representative, deeply dysfunctional, angry, and resentful ghetto king. "We are Woodson"

Of course no one bought the message. Those on the stage were creeps, misfits, and outer limit, left on the curb nobodies.

The Age Of Diversity had reached its Baroque, Rococo bathos, a period of ridiculousness and charmless, humorless belligerence. Pictures of the Woodson graduation went viral on social media, bald examples of excess and silly presumption, The end of a soppy, lame, and ignorant era was nigh. Goodnight Moon, goodnight preposterous staging.

Fat Betty graduated with honors - only because the school wanted to make her an example of diverse excellence - and went on to secretarial school, got a job in an HR department to enter data on virtual spreadsheets, married a fatty like her, had children, and led a modest, unremarkable life. The sheen of special status has been quickly graffitied and marred once she left Woodson, so she didn't know what hit her once she sat in her cubicle at Marker Brothers. She was in a dull job, a fat girl with no romance, and sold a bill of goods by her former proprietors of good.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.