Harrison Bunker was approaching what would likely be his final decade, and like all who reach that milestone was reflecting on the past. From Bravo! to What was it all worth?’ men can only be jittery at the thought of demise - at best with some ceremony, he did this or that; at worst with nothing more than a fare-thee-well, flowers, and an obituary.

He looked back on his life with some indifference - his life had been one of moderateness, neither particularly noticeable nor unrecognized, an ordinary life with some good fortune. Bella from Morocco, for example, who had dropped into his lap like a magnolia blossom, fragrant and delicate. Or some intuitive foresight and moments of literary vision, or fatherhood, but all in all he rarely veered off center, came out pretty much as would have been predicted for someone from a middle class, midrange, average family like his.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich is Tolstoy's story of disillusionment. Ivan constructs a perfectly ordered world to live in - family, occupation, club, and associations all chosen and configured to avoid interruption in what he imagined would be a simple, unadorned, but trouble-free life. Emotional attachment and intimacy were his enemies - distorting, bothersome features of life which he wanted to avoid, His would be a sail on an even keel with favoring winds.

Life of course is not so easily managed, so when he is diagnosed with a terminal illness, he is flabbergasted. This of all things was not supposed to happen, and having gone through every Kubler-Ross phase of denial, rejection, hostility, and anger, he is left with only the horrific idea of extinction. In the end when Death comes, he looks, smiles, and says, 'Death, is that all?' a final epiphany. It is not death which is terrifying, only the idea of it.

So, this was what Harrison reflected upon - not the life he was leaving but the unholy prospects of what was to come. Ivan Ilyich in his final days realizes that what he had constructed was a straw house, a house of cards, insubstantial and hopelessly vain. Not only did his careful crafting not prevent his current demise, it made him irrelevant, supernumerary. He not only cared little about his wife, family and colleagues; but they cared even less about him.

Harrison's doctor told him he was in fine form with the prostate of a forty-year old, the heart of an athlete, the mind of a poet. 'Numbers don't lie', Harrison replied, and with that number in his mind when he first woke in the morning, he could only count the days.

His wife, practical and actuarial in her bones, demurred. He would live well past his presumed pull-by date; but whether ten or twenty years, the difference was insignificant.

'The end is nigh' said the cartoon signs of the wandering ascetic. Time to leave gas mileage and grouting behind and prepare for....For what? he asked, neither religious nor Stoic; and so it was that he lingered among his crotchety, creaking peers, hoping like Ivan Ilyich for some kind of reprieve.

The time for reprieves, however had past. There were no more December-May affairs, no more aspirational hopes for longevity, no more shots in the magazine.

But what about that storied wisdom that grandfathers are supposed to have? That history repeats itself? That human nature is ineluctable? That, as the scholar Jan Kott knew well, if you laid down all of Shakespeare's Histories in chronological order, you would find nothing new from king to king, generation to generation. The same palace intrigues, jealousies, rivalries, envy and hatred would be played out endlessly with only the actors changed. Only the way they behaved would be interesting and fit for melodrama.

What about unalloyed, uncompromising love? After a long life of internal squabbles, deceit, and misanthropy didn't grandfathers become unequivocally non-judgmental and loving? The record concludes nothing of the sort. Old people are left out to dry for the most part, like Lear on the heath, abandoned by his daughters to die, or granny-dumped by children anxious to move on without the harping and hectoring of aged parents.

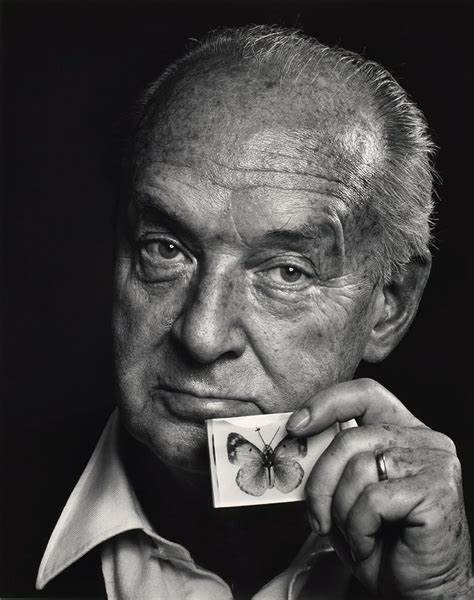

What was left, then? Vladimir Nabokov was a self-described memorist. From an early age he knew which events were important to remember; which were extensions of who he was becoming; and in Speak, Memory he writes of Cannes, Deauville, and Venice, hotels and beaches, elegant women and his mother's beauty. The present exists only in milliseconds; the future yet to happen so it is only the past that defines us, the only real substantive clue to the fact that we ever existed.

Yet Harrison had no such memory bank, no mnemonic clues to his existence. His memories were fragmentary and random. They no more defined him than a hurriedly sketched caricature.

As he approached the end of his life, the hoped for epiphany was long in coming. Hindus had the right idea - enlightenment begins at birth and passes through four distinct phases - student, householder, recluse, and ascetic wanderer - and only the most evolved and most mature can ever reach the final abnegation of self and the merging with the eternal,

Here he was, a foundering, lost soul without religious moorings about to set off on his last sail without anyone to reef and unfurl the canvas.

He had a few coat-hangers left - a few desultory friends, old classmates - but the cloakroom was not where he wanted to be. It was a dismal place hung with shabby jackets. Yet there was no other comfortable room to rest before...

Here, as always, he paused his train of thought. The unthinkable would be around the bend if he continued.

And so it was that Harrison Bunker ended his days. Unsure, uncertain about what was to come, not with the equanimity he had hoped but with some measure of acceptance. It wasn't so much about how he would be remembered, but how he approached his own demise.