“There are all kinds of love in this world but never the same love twice"- F. Scott Fitzgerald

Harrison Baedeker had known real love once in his life, and could never forget her. Smitten, he could never move beyond her, never proceed beyond from what Turkish poets call aşk - romantic, sexual, unforgettable love to sevgi - mature, permanent, longstanding affection.

As a result, he remained single, hopelessly romantic, and emotionally desperate. If he had had love once, he could have it again. Was there no room in an infinite universe for more of the same?

F. Scott Fitzgerald had said in The Rich Boy, a winsome story of lost young love, 'There are many loves in the world but never the same love twice', a note of pessimism for the loss of first loves, and a greyish optimism for the more ordinary loves to come.

Baedeker had read these lines as a young man, and had excepted himself - his was to be a life increasingly passionate loves, each more fulfilling than the one before. The dull, compromised, deadly prospect of a long marriage would not be for him. His first love could be and would be recreated, reproduced....he could not find the right words... for the romantic series of loves to come.

Fitzgerald's story left some doubts as to its meaning. Were men so fanciful and commandeered by romantic love that they would be forever in Petrarch's traces? Condemned to a life of frustrated desire? Or were they Stoics, persuaded that love comes in all shades, none special, all unique only because of the particulars of shade and shadow?

This unforgettable first love was Nancy Bell barely thirteen and in the seventh grade. Nancy was different, Harrison told his friends many years later. She was....and here he always paused because words failed him when he tried to explain exactly what it was about the girl that he found so appealing, so much so that he never forgot her; but she was inexplicable, that was all he could manage; and unless you had such a love, you would never understand.

He remembered the time when he and Nancy went into the woods behind his house. She took his hand and they found a ferny, place, one which he had found when he was still tracking rabbits and foxes. 'Here', she said, and pulled her dress up over her head and stood naked as the water droplets from the ferns dripped onto her face and arms. “They are my jewels”, she said to him, “and one day you can buy me real ones.”

It was cool and dark in the woods behind his house. Harrison's father had said that he would cull the deep grove before it got too overgrown but he never got around to it, so the ferns had grown taller than him, and only rabbits could find their way through the bramble bushes. Once when he was little he got lost in the woods and thought he would never find his way out. There were bears and wolves in the woods, and he might wander for days without finding his way home.

For years he never set foot in the woods until Nancy Bell had asked him. He knew that there were no wild animals there, but he always hesitated at the mountain laurel bushes at the back of their yard, and never took the narrow path into the woods. That was how childhood worked, he later thought, full of crazy imaginary things that scared you, and one day you woke up and they weren’t there any more, and the woods was just a dark, wet place where you would prefer not to go.

Nancy Bell sat next to him in school the next day, so close together in the auditorium that their legs touched. She smelled fresh and clean, like talcum powder and lilac soap, and she was wearing the same dress that she had worn in the woods. He noticed a bit of dried oak leaf on her dress that she had not seen and remembered how she had put her clothes neatly in a pile on a mossy patch under his father’s favorite tree.

In June before the mosquitoes started biting, they sat naked in the woods and told stories to each other. Nancy made up the rules and said that no story could be about their parents or brothers and sisters. “Make them up”, she said. “Make everything up”, and so each afternoon before the mosquitoes hatched from the wet oak leaves and puddles where the rain sluiced down the tallest trees and collected beneath them, they invented places where there were no people but people-animals “Your house has disappeared”, Nancy said, “and so has mine. All we can see is the trees and the squirrels. I have made everything outside the woods disappear.”

Harrison compared every woman he met with Nancy Bell; and they never measured up. They were either too matter-of-fact or too determined; too focused or too deliberate and precise. None had Nancy’s ability to change things to suit her or to make things go away. Henry was never fully aware that she was doing this to him, making his choices for him; and when he once considered it, he laughed. They were only children, after all, and one summer with Nancy Bell was nothing. So what was it, then?

'Arrested development', said a friend who had never been corralled by anything and went from bed to bed without one single arrière pensée but with consummate appeal. Fitzgerald was a hopeless romantic, he said. There are no Gatsbys, no rich boys' laments. All for one and one for all, 'and you, my friend', he said tapping his finger on Harrison's chest, 'need to get with the program'.

One year he arrived late at night to find the one hotel at the bend in the Niger full except for the Emperor's Suite, water view as advertised but unfinished and unscreened but right next to him in the adjoining room was Bridget from Cork who sympathized with him and said her large airconditioned suite was big enough for two.

Or Fatimah from Izmir, great granddaughter of the last Ottoman sultan, his guide to Ephesus and Antalya, who 'understood' him; but foreign dalliances have their life in foreignness, and when he returned to New Jersey, they were irrelevant.

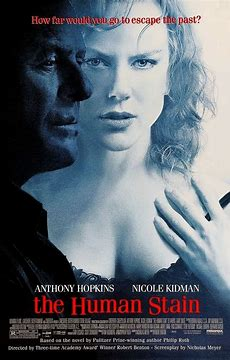

The Coleman Silk character of Phillip Roth's The Human Stain said to a friend who challenged him on the wisdom of a December-May affair with a low-class, abused woman, 'Granted, she's not my first love; and granted, she's not my best love; but she certainly is my last love. Doesn't that count for something?'

Another take on Fitzgerald. Who cares of what one's last love is made? It has importance only because of its place in the serial; just as first love must be recognized. Silk had led a long, loving (Turkish sevgi) life with his wife, one more of accommodation than passion - he too had never forgotten his first love - but now at the end of his life, comparisons were not valid. A thirty-something lover would never be like a wife of fifty years, nor should she be. She would only be a portal to something different, a clue to an aspect of life overlooked.

Harrison Baedeker should have had some of Roth's wisdom. As it was, he moped. Time and again he was tempted, but women would never measure up. Solitude with pungent memories of Lucinda, his first love, were preferable to social concubinage - an unfair but accurate description of his idea of marriage. In current terms, his virtual love was as real and consequential as any other flesh-and-blood representative of women.

There was one woman who pushed all the right buttons, who challenged his celibacy and solitude as arrogant reprisals. In other words, 'Man up', get on with it, and so what if we're not soulmates’, she said. 'We're in the same boat'; but as hard as he tried, he couldn't shake the image, dream, specter...again words failed him… of his first love.

Consigned, he said he felt, marginalized, and trapped. The world with all its first-come-first-serve sexuality, johnny-come-lightly liaisons, come-ons and brush-offs had left him befuddled. Not only was he beholden to a romantic wraith of decades past, but he was ridiculed by new-gen X sexual adventurers.

Some of these women fell in love with him - whatever that meant - and he was surprised at the afternoon soap's tears, pleas, and 'please don't leave me' entreaties, but still, he decided that enough was enough.

There is no moral to the story. Each to his own. It would be satisfying to the many who value love and see it as a human given, to view the solitary end of life of Harrison Baedeker as confirming of the old, tried and true Biblical injunction 'Be fruitful and multiply', and the hundreds of years of poetic affirmation of love. He was a wasted caricature of the social outlier - bereft, uncared-for, alone, and desperately unhappy.

While Harrison had his doubts, his friendships with the old ladies of his retirement home were satisfying enough to at least shelve his regrets; and his nieces, nephews, and old retainers were very happy when his will was read.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.