Ivan Karamazov, Dostoevsky’s character in The Brothers Karamazov, explains to Father Zossima why he believes that the state should be subsumed within the Church. How little crime there would be, he said, if men were beholden to first to God, the final arbiter of right and wrong. Crime – sin – would be punished at Judgment Day, the consequences of ill deeds far more lasting than any secular punishment.

But far from a desire for a punitive religious state, Ivan only understood the centrality of a moral ethos at the center of any state - that governance is simply not possible without the universality of core ethos to which everyone subscribes, an ethos of honesty, honor, respect, courage, and compassion.

This idea is far from one of theocracy where secular governance ceases to exist and only the church remains to enact its Biblical or Koranic rules. Ivan recoiled at the accusation and insisted that without a moral core, a nation would become only a fragmented, querulous, divided place.

The values of honesty, honor, respect, courage, and compassion predate Christianity, of course. The diptychs of Cato the Elder (234-149 BC) included in a curriculum for future Roman leaders stressed the same ideals. A good Roman consul or even Emperor needed to have more than good management, military strategy, and administration to rule well.

In other words, Roman-Judeo-Christian values are universal and ex-temporal. No successful civilization has ignored them; and most have incorporated them in education and civic life. Teaching – insisting upon – these values would strengthen a moral ethos if it existed and help promote one if there were not.

The United States, of course, has fiercely defended the separation of church and state and insisted; but the intent of the Founding Fathers has been misinterpreted ever since the framing of the Constitution. Jefferson et al were never against the incorporation of and respect for religious principles within a secular state; just that no religion should ever be imposed on anyone.

The principles of the Enlightenment on which both the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights were based were profoundly religious. Although philosophers of the 18th century valued logic and rationality above all, they were insistent that they be put to use in the service of God. They like Augustine and Aquinas before them understood that the way to faith was through logic; and while faith would always triumph, the exercise of reason would strengthen belief not diminish it.

Today, however, these Jeffersonian principles have been deformed into policies which forbid the inclusion of religion in any secular institution or debate. As a result the teaching of Judeo-Christian moral and ethical standards find no place within schools at the very moment when they are most needed.

Identity politics which favors self-interested separatism instead of social and philosophical integration are corrosive and dangerous to the body politic. Pride in ethnic, gender, or racial identity in and of itself is not dangerous; but when self-serving, often venal, principles replace common, mutually-respected values, there is indeed a problem.

Augustine’s work, The City of God is perhaps the most important Western work on the relationship between church and state. As a good Christian who evolved from doubting roots into Christianity’s most influential theologian, Augustine argued for the co-existence if not integration of church and state. As a good Christian, he believed that nothing was possible without faith – not civil society, not government, not family or community. Faith precedes logic, civil discourse, laws, and governance, he said. Without it, mankind would be lost.

A young woman I know grew up in a religious family. Neither evangelical, fundamentalist, Opus Dei, or Hasidic but simple believers in God, his generosity, forgiveness, and divine care; and at every meal, the family said grace.

Bless us, Oh Lord,

and these thy gifts which

we are about to receive from thy bounty,

through Christ, Our Lord.

Amen.

A simple prayer of thanksgiving, a statement of faith, an acknowledgment that both they and the food on the table were gifts, a blessing from God. Gifts, however, can be taken away; and saying grace was both an expression of gratefulness for God’s attention and an implicit promise to honor and respect him.

After a while the prayer became so routine that it was simply part of the meal, but it’s meaning was never ignored. It was a salutation, an introduction, and a short note of spiritual purpose and belonging; and no matter how often it was repeated, neither Laura nor her family could ever entirely dismiss it.

Grace was never an imposition but a privilege. Praying at the table not only joined the family together, but joined them in the larger communion of believers. There was a unity in faith, and although they did not attend church and were as suspicious of the megachurch revivals organized to physically unite the faithful as their secular friends, they felt that their simple family prayers were even closer to Christ’s ideal than any more public, mass expressions of belief.

It is this sense of community, reflected in the universal recitation of grace, which is relevant to secular society; and was in this spirit that Dostoevsky through his character Ivan, proposed a particular integration of church and state.

The fact that America is divided, fractious, and angry; that identity groups increasingly and often violently demand their rights; and that consideration of the commonweal and respect for national integrity have become secondary is no longer news. In fact, the most common adjective to describe the country and its current state of affairs is ‘divided’. Yet despite the lament, few are willing to give up their demands.

Not so many decades ago, Americans did espouse a universal ethos – in fact that written into the Bill of Rights by Thomas Jefferson and his colleagues. Americans were granted the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness by their Creator; and were therefore both fortunate for the gift, and responsible for its stewardship. The pursuit of happiness never meant the right to individual satisfaction per se but only within the context of the larger community of which the individual was a part.

No activity therefore could be excluded from the framework of God the Creator and Man the Executor. Jefferson of course never had the imposition of any religion in mind when he wrote those words; but only that a good citizen should be mindful of his origins and his responsibilities to himself, his community, and his nation.

A universal belief in God, and in the case of 18th century America, a Christian God, was central to the new republic. The values, traditions, and expectations of Christianity were commonly recognized and respected. There was more to being an American than just being an individualist, an entrepreneur, or a free citizen. Americans from one end of the continent to the other subscribed to the same principles, adhered to the same beliefs, and acted according to the same code.

More or less, of course. America has also been a lawless place of Robber Barons, Wild West cattle thieves, Wall Street manipulators, dirty politics, and greed.

Yet it has been because of a disrespect for this common, universal code of right behavior and justice that the country has veered from its Jeffersonian beginnings. There might have been no way for the ethos to have survived periods of great opportunity, the chance for great wealth, land, and property. Erosion of common values might be the inevitable by-product of individualism and individual enterprise.

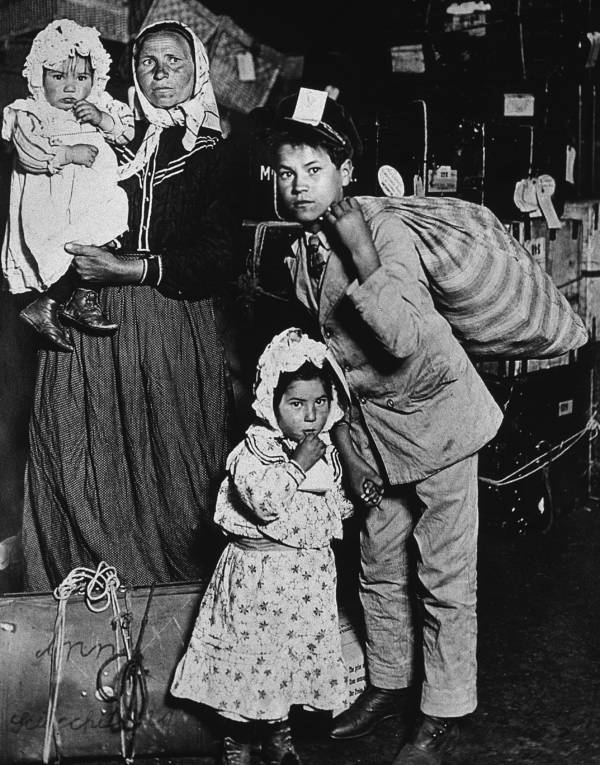

The erosion of this national ethos, or national philosophical culture, has been accelerated not because of increased immigration and the introduction of cultures and beliefs far removed from our early Christian heritage, but because these cultural identities have been given a special, unique status never before seen in America. In previous decades of immigration to America, new arrivals were expected to quickly assimilate – to speak English, to respect not only the laws of the land but its traditions and values, and to become as American as those born here. Not so now.

At its most general, grace is simply a way of becoming more committed to universal values, and through the profession of this commitment, engaging others. Not quite a radical movement by today’s standards, but a movement nonetheless.

Perhaps it is time to reconsider the separation of church and state - a compelling argument for moral authority.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.